Nick Carne

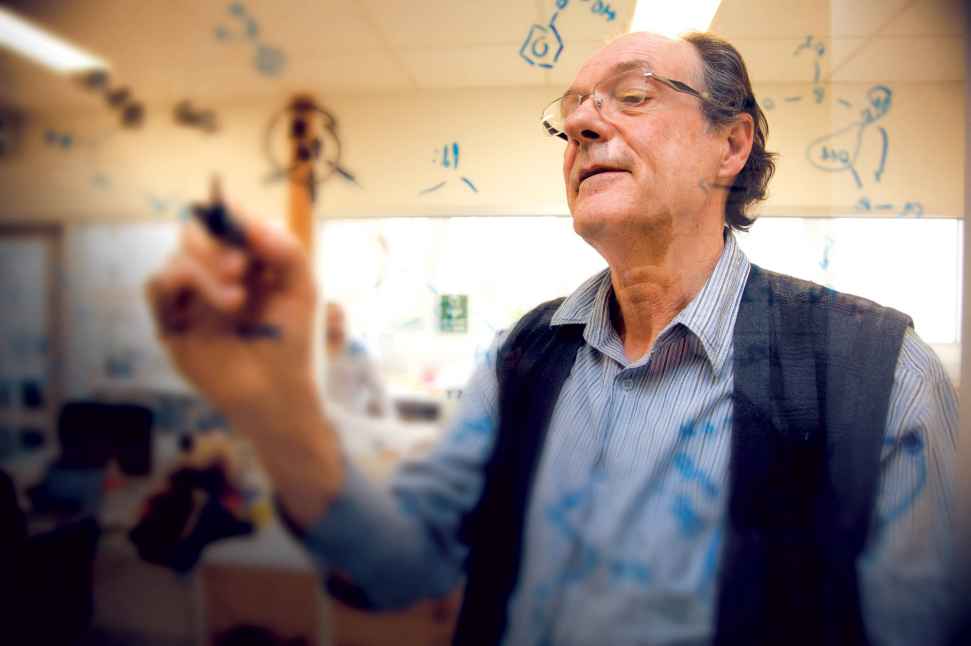

CLEAN, GREEN

CHEMICAL CRUSADER

—

Meet the pioneering professor who’s helping industries switch to cheap, environmentally friendly technologies to reduce energy use and waste.

Professor Colin Raston and his colleagues made international headlines in 2015 when they proved the impossible was possible – you can, in fact, unboil an egg.

But Professor Raston reckons he’s done even better work since. That’s not an idle boast, it’s just a reflection of how important and valuable this ‘unboiling’ technology is, and will continue to be, for many different industries.

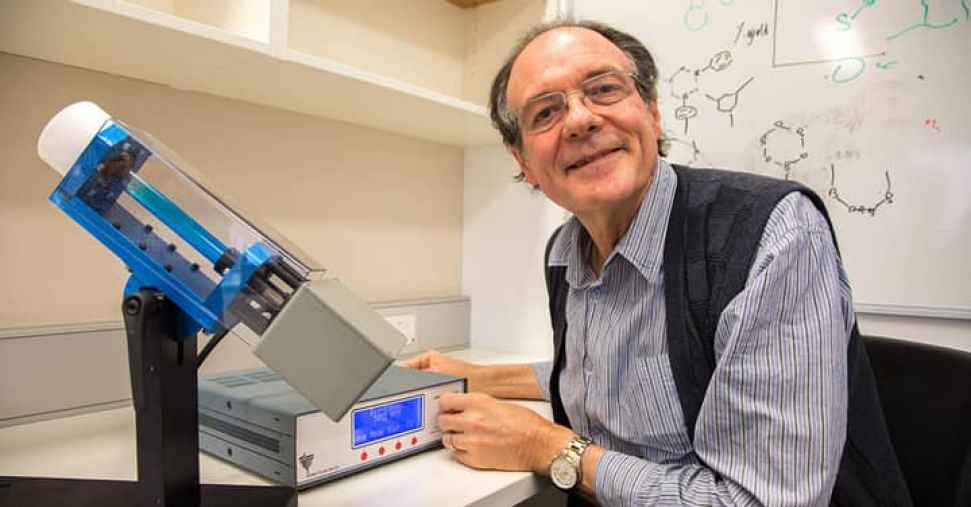

The Vortex Fluid Device (VFD) he invented to pass the time on a 15-hour flight has revolutionised flow chemistry, in which chemical processes occur in a continuous flowing stream. The VFD can rapidly create a range of chemicals in water and other non-toxic liquids, significantly reducing the cost and environmental harm in a range of chemical processes.

It looks and is deceptively simple to use. All you see is a tube that spins at very high speeds and at a variety of angles – but it has created a new paradigm for how things are done in the chemical and biological sciences, as well as materials processing.

“You can make complex organic molecules. You can use it for drug delivery, for making tools for imaging. It covers food processing, we’ve got projects going in wine processing, and I’m just going through the first paper on fish oil encapsulation at nanometre dimensions,” says Professor Raston.

“We can use it to cut carbon nanotubes without using chemicals, exfoliate graphene from graphite without chemicals, and to make graphene oxide with zero waste – which is a big deal,” he adds.

Professor Colin Raston FRACI CChem FRSC is a South Australia Premier's Professorial Research Fellow in Clean Technology. He completed a PhD under the guidance of Professor Allan White, and after postdoctoral studies with Professor Michael Lappert at the University of Sussex, he was appointed a lecturer at The University of Western Australia (1981) then to Chairs of Chemistry at Griffith University (1988), Monash University (1995), The University of Leeds (2001), and The University of Western Australia (2003). He is a former President, Queensland Branch President, and Chair of the Inorganic Division, the Royal Australian Chemical Institute.

“Why haven’t we been told about green chemistry before, where can we find out more information?”

Using it to unboil an egg – by refolding the proteins into the state found prior to cooking – was a nice bit of theatre, and not surprisingly won an international Ig Nobel Prize in 2015. As the Ig Nobels describe themselves, they aren’t about crazy or pointless science, but about “honouring achievements that make people laugh, then think”. And Professor Raston has been making people think over his whole career.

The VFD brings together his two passions: scientific innovation and green chemistry. For more than 20 years he’s been championing the importance of chemists developing products and technologies that don’t create large amounts of waste or require unnecessary energy in their production. “Green chemistry is all about reducing the negative impact on the environment,” he says.

In the early days, there were many cynics who doubted the value of spending time and effort on developing more sustainable chemical practices. “I thought, at one stage, my career was going to go down the gurgler,” Professor Raston admits. “But the younger generation were saying ‘Why haven’t we been told about green chemistry before, where can we find out more information?’”

It was this that encouraged him to persevere.

Fortunately, Professor Raston found some like-minded souls to work with. In 1991, two scientists from the US’s Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) released their 12 Principles of Green Chemistry. They then invited him to represent Australia at a high-powered roundtable meeting in Washington, DC in 1998, which was designed to get people thinking.

Since then, more sustainable chemical practices have become not just a reality, but the accepted norm, required in most grant applications. Professor Raston says that nearly everyone who attended the roundtable in the US has since been honoured by their governments for their contributions to the industry. He was appointed an Officer of the Order of Australia (AO) in 2016.

“It’s all happened in the last couple of years,” he says. “Now there are lots of international conferences.”

Most significantly, it’s shifted the mindset, he says, particularly with the younger generation of scientists. Whereas in the past, a chemist might have used a highly toxic organomercury compound to solve a problem, now they’d think twice. “They’d say, ‘Hang on, as chemists we’re supposed to be able to come up with alternatives,’” he says.

For Professor Raston, a focus since moving from the University of Western Australia to the Flinders College of Science and Engineering in 2013 has been scalability: how he can scale up green processes developed in the lab to an industrial level.

His lab has already published more than 60 papers on the use of the VFD, and is collaborating with other universities in Australia, the US and Europe. It has two joint patents with the University of California, Irvine, focused on the multi-billion-dollar pharmaceuticals industry, not to mention a number of other patents, too.

Things are now moving rapidly. In June 2018, Flinders University and ASX-listed company First Graphene formed 2D Fluidics – a business that will both produce environmentally safe supplies of high-grade graphite and make the VFD technology commercially available.

“It’s easy to use – just plug and play,” says Professor Raston.

Donate to research

Through research, and research-led teaching, we build and develop the knowledge and capabilities that improve lives and enhance society as a whole. Your gift can help support our projects, which are finding practical solutions to real-world challenges and create hope for a better future.

![]()

Sturt Rd, Bedford Park

South Australia 5042

South Australia | Northern Territory

Global | Online