Laetitia Laubscher

THE CHANGING FACE OF GLOBAL SECURITY

—

Transnational crime has grown exponentially, thanks to globalisation, the booming illicit drug trade and the emergence of new cybertechnology.

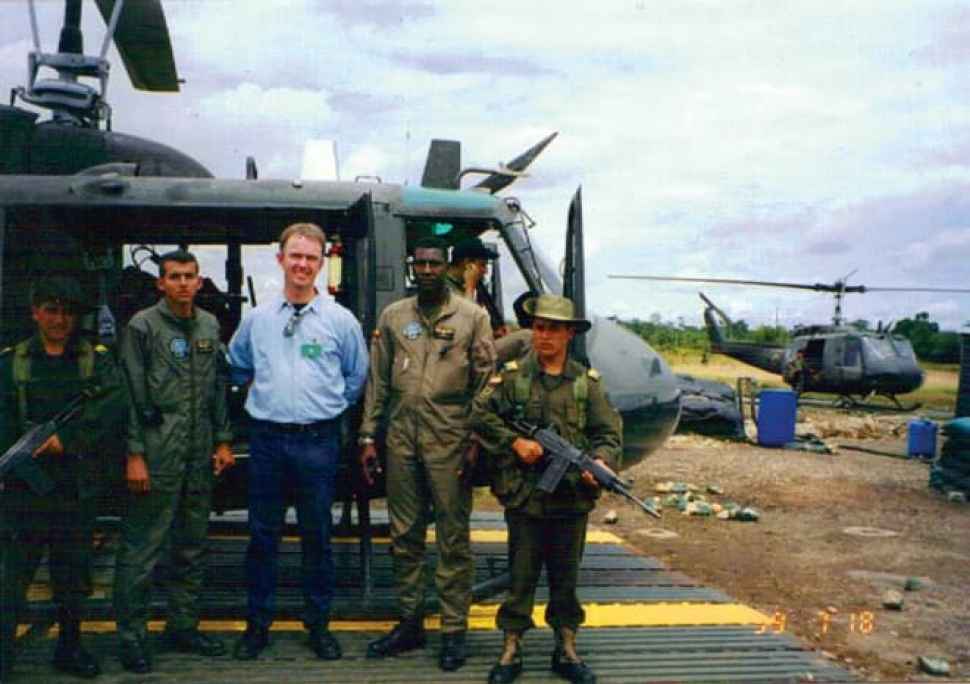

Professor Andrew Goldsmith started investigating transnational crime more than two decades ago, after having witnessed first-hand the impact of the drug war in Colombia.

He’d been invited to the South American nation after members of the Colombian Ministry of Defence read his book, Complaints Against the Police: The Trend to External Review, and invited him to assist in their police reform process.

Many of the events now portrayed in the Netflix hit Narcos occurred while Professor Goldsmith was in Colombia. He met the real Attorney-General Pablo de Greiff and Rosso José Serrano, who became the General of the National Police and a fundamental player in dismantling the notorious Cali Cartel.

When on the frontline in Colombia, Professor Goldsmith realised that more research was needed on transnational crime, which was a relatively underappreciated criminal activity at the time. “You can’t talk about police reform in a country like Colombia without reckoning with the enormous distraction of, and effort involved in, fighting the drug war,” he says.

The former lawyer is now considered a leading expert in the field.

Trained originally as a lawyer, I spent nearly three years in legal practice before undertaking postgraduate studies in the United Kingdom and Canada. That further study was in the fields of law, criminology and social theory. My first teaching position was at Warwick University where I taught criminal law and criminology. I moved then to Brunel University, London, and then to Monash University. I joined Flinders University for the first time in 1997 as Foundation Professor of Legal Studies. Between 2009 and 2012, I held the position of Executive Director, Centre for Transnational Crime Prevention, University of Wollongong. I re-joined Flinders in late 2012 to take up my current position.

“The global demand for recreational drugs has had an extraordinary impact on criminality and law enforcement and the scale of criminality in countries across the globe.”

As Strategic Professor in Criminal Justice and Director of the Centre for Crime Policy and Research at Flinders University, he is also co-editor of the Australian and New Zealand Journal of Criminology, and has authored numerous journal articles, reports, chapters and books on the subject.

While transnational crime is keeping Professor Goldsmith busy today, the concept is a relatively new one in terms of how governments around the world are dealing with it.

The United States first recognised transnational crime in the mid-1970s, but it wasn’t until 1995 – around the time that Professor Goldsmith was in Colombia – that the UN issued its official definition as “offences whose inception, prevention, and/or direct or indirect effects involved more than one country”. It identified 18 categories of transnational crime, including human, drug and arms trafficking.

Since 1995, transnational crime has grown exponentially, spurred on by globalisation, communication and mass migration. The cost of transnational organised crime is estimated to be about 3.6% of the global economy, with about 20% of that coming from the illicit drug trade.

“The global demand for recreational drugs has had an extraordinary impact on criminality and law enforcement, and the scale of criminality in countries across the globe,” says Professor Goldsmith.

There are two major challenges in tackling transnational crime: bureaucratic issues, such as the division of responsibility between agencies in different jurisdictions and even within the same jurisdiction; and the effects of cyberspace, which make tackling transnational crime particularly difficult.

“The evolution of the internet – social media technologies, encryption technologies, digital banking technologies – have all created new pathways, new skill sets, new opportunities,” says Professor Goldsmith.

This has led to the emergence of new types of criminals, as well as new criminal methods, such as the Mafia using encryption technologies to conceal their communications from law enforcement.

The current model now used to combat transnational crime is not entirely fit for purpose, even when there are successful arrests and prosecutions.

“The big investment is in law enforcement – the attempt to deter and prosecute offenders,” says Professor Goldsmith. “But it hasn’t stopped the rapid replacement of those openings by other groups. Police increasingly say that in some of these areas, ‘We can’t arrest our way out of these problems.’”

Research efforts by Professor Goldsmith and others are key to analysing both the efficacy of the current enforcement measures taken, and to understand the drivers and underlying causes of the crimes themselves. The hope is that, with better understanding, we can address the issues in a more holistic and preventative way.

Flinders is now running a longitudinal study on the role of the internet in recruiting adolescents into crime, as well as an interview-based study looking at offenders’ relationships with guns.

The insights will be crucial for Australia in its efforts to enhance global security, while also protecting Australian communities.

“There’s a lot that’s going on offshore that we don’t consider or appreciate enough, but that’s the case equally at home,” says Professor Goldsmith.

“Ice is brought from China into Australia and sold by motorcycle gangs, or distributed by them across rural and regional Australia. The effects on families as well as individuals is quite striking. There’s a connection between harmful things in our own backyard and transnational crime.”

Donate to research

Through research, and research-led teaching, we build and develop the knowledge and capabilities that improve lives and enhance society as a whole. Your gift can help support our projects, which are finding practical solutions to real-world challenges and create hope for a better future.

![]()

Sturt Rd, Bedford Park

South Australia 5042

South Australia | Northern Territory

Global | Online