Eye see a better way

Is there a way to diagnose autism in infants by looking into their eyes? Caring Futures Institute research is breaking ground on retina examinations to spot differences in ERG waveforms that could help identify autism and other neurodevelopmental conditions earlier.

The red, double decker number 19 bus stops and starts its way through London’s busy streets. Miles has a thing for buses; the numbers, the timetable – the certainty that after Haymarket there’s Piccadilly Circus. First Hyde Park Corner. Then Knightsbridge station. Dr Paul Constable, Miles’ dad, remembers one trip on the number 19 bus above all others. The one when Miles cried and cried, inconsolable the whole way home. The one back from his first trip to the optometrist.

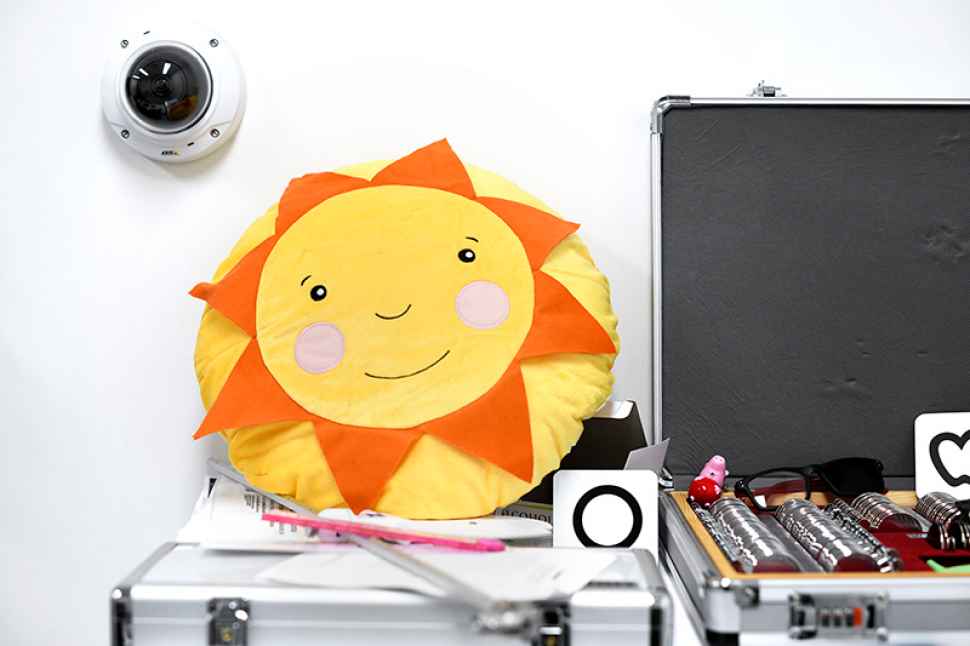

Image above: Jane and her son Ned met Dr Paul Constable at Flinders Vision’s autism-friendly optometry.

Miles was seven years old – a long time to wait for an eye test if you consider his dad is an optometrist, a vision scientist, and has worn glasses his whole life. For Paul and Helle, Paul’s wife and Miles’ mum, an eye test wasn’t at the top of the priority list at the time. Miles was diagnosed with autism when he was three years old and it was a difficult time for their family. Since his diagnosis, they had been busy with psychology and speech pathology sessions while juggling a PhD and clinical practice.

At the optometrist, they had put dilating drops into Miles’ eyes. His vision blurred and his eyes became incredibly sensitive to light. The disorientating side effects last up to three hours but Paul struggled to convince Miles that it was temporary. For Miles, he couldn’t see the bus numbers anymore and through the blurriness felt like his whole world was gone.

On that bus ride home, Paul decided there had to be a better way.

Source: AutismSA

Source: The Medical Journal of Australia

Dr Paul Constable and son Miles (aged six) in Hyde Park in 2006.

“I really just wanted to prevent other people from having the traumatic experience that I did.”

- Dr Paul Constable

Better vision

Ned’s first visit to Flinders Vision (now known as Health2Go) was an unrecognisable experience by comparison. Paul had moved his optometry practice, studies and family to Adelaide where he later helped set up a new autism-friendly optometry service at Flinders Vision – the first of its kind in Australia. Paul considered the eye testing process, subtle aesthetic changes to the room (some as simple as covering machines with a blanket) and utilised new technology in the form of the handheld autorefractor which allowed eye testing to be done from a distance.

Ned’s mum Jane heard about Paul’s autism-friendly eye tests through a friend at school. Ned is on the autism spectrum and Jane knows new environments can be difficult for him. When they arrived and met Paul, they followed the colourful floor pads placed from the waiting room to the consultation room – like a treasure hunt. Paul took the time to explain the handheld autorefractor to Ned, “First I’ll hold this towards your mum to see her eyes. Then I’ll hold it towards you to see your eyes.” There were no intrusive and intimidating devices pushed up to Ned’s face, no dilating drops and no blurred world for Ned. When Paul told them they were done, Jane thought “Was that it?”

Paul’s childhood memories of optometrists were as distressing as Miles’. He set up the autism-friendly consultations at Flinders Vision for the same reason he studied optometry: “I really just wanted to prevent other people from having the traumatic experience I did,” he explained. Since it began, Paul and his colleagues – trained in autism-awareness – have seen more than a hundred children with autism. Kids who are likely to have never had an eye test and maybe otherwise wouldn’t.

Images above: the non-invasive RETeval scanner (top) and child-friendly objects used during vision examinations.

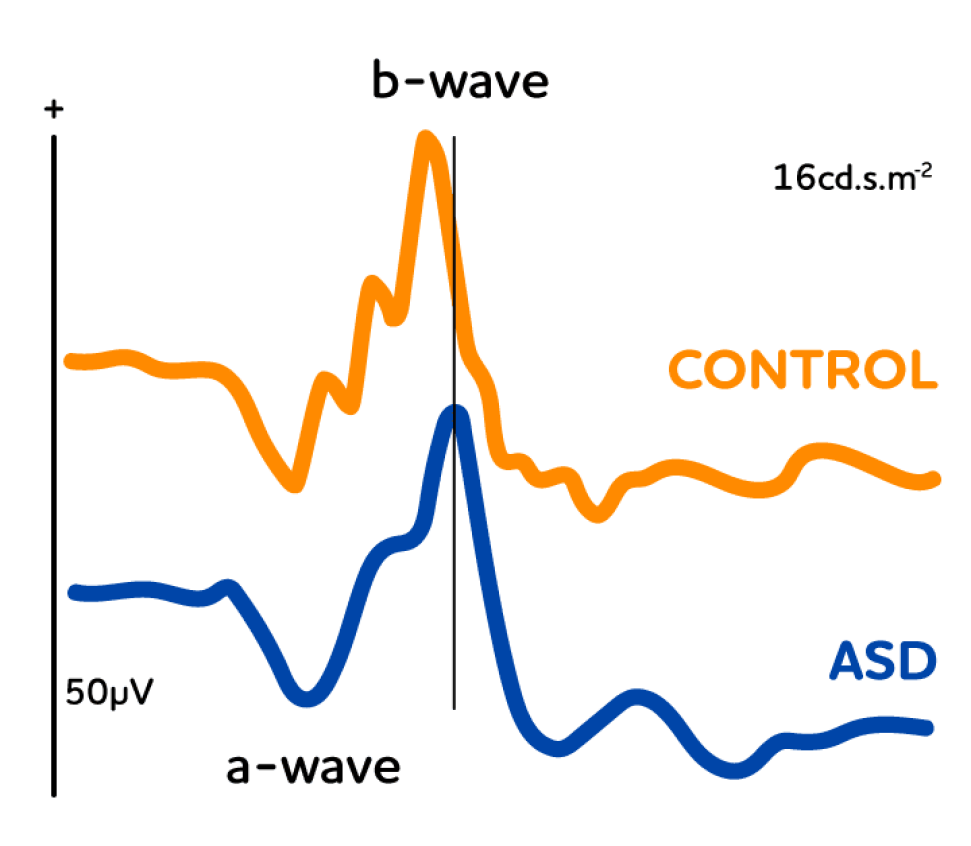

An MRI scan is a common way to examine brain activity. Eyes also provide a window to the brain with retina examinations, like in Paul’s research, offering another way measure brain activity.

Better start

Kids on the autism spectrum, and their parents, spend plenty of time in clinical settings. Jane started taking Ned to a speech pathologist when he was two and a half years old. Specialists hadn’t diagnosed Ned on the autism spectrum but recommended speech therapy for language understanding problems. Ned attended weekly sessions for the next year and Jane saw the difference they made. Important services like these could have been funded with an autism diagnosis.

Paul describes Miles’ speech pathologists as angels. “Speech therapy was where we saw the most change,” Paul explained. The early years are the most influential in helping a child on the autism spectrum develop language and social skills. Both Miles and Ned had a good repertoire of words – something that may have led professionals to overrule their parents’ questions about the possibility of autism. As parents, they knew their boys had the words but saw their difficulty in using them with context.

“I didn’t need a diagnosis or a label,” Jane explained, “but I knew something wasn’t right. Ned’s a quiet kid and I worried at school he’d fall through the cracks.” She pushed for reassessment and when Ned was five and a half years old he was diagnosed on the autism spectrum. Seeing Ned at school now she’s glad she did. Ned’s got a great group of friends and he’s got his younger brother Fletcher who’s always by his side. “Ned’s teachers are really supportive too,” Jane said, “which I think is because they have a better understanding because of his diagnosis.”

Better way

Miles’ diagnosis helped Paul and Helle understand a lot of what was happening when Miles was a baby too. At the time, Paul was three years into his PhD at City University of London researching the blood brain barrier. He was using electroretinography (ERG) as a window from the eye into the brain. Paul spoke to colleagues about autism and remembers the day he told his research supervisor Professor Geoffrey Arden about Miles’ diagnosis.

“I told Geoff and he immediately said ‘Autism is neurodevelopmental, let’s google who has done an ERG research related to autism’”. Only one person had, in 1988, and so Geoff turned around and simply said, “That’s the research you must do.”

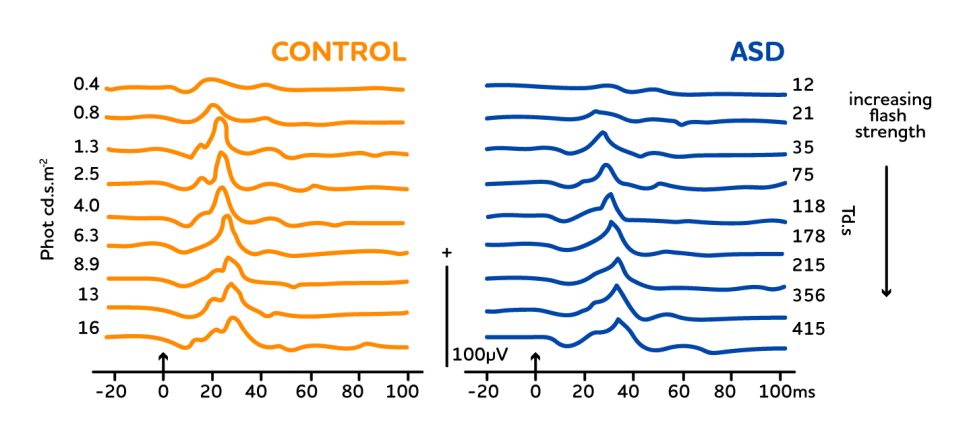

For the next 13 years, that’s exactly what Paul did. He fought for funding, he fought ethics boards and chased new technology while conducting research in conjunction with Yale University in the US and City University of London in the UK. One of the greatest advances came in the form of the RETeval, a small, handheld device which could read the retina’s response to light by placing it up to the eye for just 45 seconds.

The RETeval allowed more mobility for testing making the trials easier. Importantly, this meant they did not need to use the dilating drops on participants. RETevals were purchased for the three locations allowing the study to compare the ERG waveforms of 89 people with autism and 87 not on the autism spectrum.

ERG waveform differences had previously been detected in other disorders affecting the brain like schizophrenia. Autism is a neurodevelopmental condition and so Paul wasn’t sure what he’d find in his research on people living with autism.

There are currently no biological markers, differences in genes or molecules, that can simply identify autism. As a result, diagnosis of autism relies on assessment from psychologists and speech therapists. When Paul’s research confirmed subtle variations in the ERG waveforms for adults on the autism spectrum he realised this could be used as a potential biomarker to help identify autism in children much earlier. It could indicate other neurodevelopmental conditions too and Paul’s research is continuing with hopes to get more data from trials with infants.

Representative ERG waveforms for a control individual and an individual on the autism spectrum. As a group, the participants on the autism spectrum had a significantly smaller and slightly delayed peak in the b-wave of the ERG waveform

Better together

For Paul, he sees this an opportunity to start important interventions like speech therapy earlier, giving parents who were in a similar situation to him better peace of mind and helping increase understanding for children on the autism spectrum.

Ned wants to be a mad scientist when he grows up or maybe an app designer or an author. “He’s a great writer,” Jane exclaimed. His biggest concern is not having enough time to do all the things he wants. Jane also worries about whether Australian society will progress fast enough to better welcome people with autism into the workplace. He has a lot to offer, he’ll just need a bit of understanding.

Miles is learning French, German and Danish and Paul says he speaks them well already. Miles hopes to use them on travels spotting his favourite cars along the Autobahn in Germany and he hopes to move back to Denmark someday.

One of the first psychologists Paul spoke to when Miles was diagnosed, who was married to someone with Asperger’s herself, told Paul something he recalls to this day. “Don’t ever underestimate what he can do,” she had said. And Paul admits, she was absolutely right.

Paul is an optometrist and holds a PhD in electrophysiology. His research combines expertise in vision science with his personal connection and interest in autism spectrum disorder. He is a senior lecturer and is the head of the optometry teaching section at Flinders University. Paul launched Australia’s first autism-friendly optometry service at Flinders Vision (now known as Health2Go) and has trained optometrists in autism considerate eye test best practices. He is researching the electroretonogram’s (ERG) differences in people on the autism spectrum and as a potential biomarker for other neurodevelopment disorders.

![]()

Sturt Rd, Bedford Park

South Australia 5042

South Australia | Northern Territory

Global | Online