In the hold

Decolonising Cook in contemporary Australian art

A Flinders University Museum of Art exhibition co-curated by Dr Ali Gumillya Baker and Fiona Salmon

Exhibition guide

Texts by Dr Ali Gumillya Baker and Fiona Salmon with additional research and writing by FUMA Collections Curator, Nic Brown

1

John Keyse Sherwin

born 1751, Sussex, England

died 1790, London, England

William Hodges (after)

born 1744, London, England

died 1797, Brixham, England

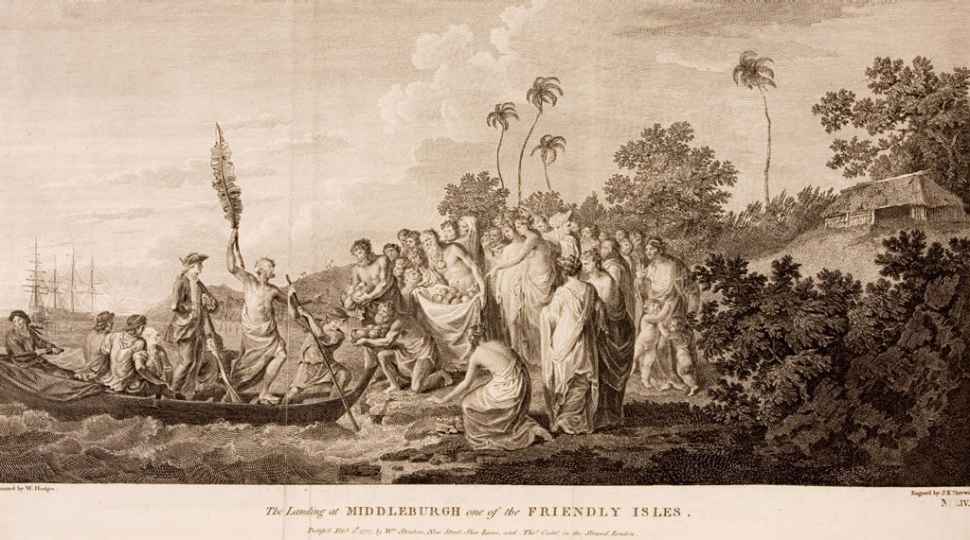

The Landing at Middleburgh, one of the Friendly Isles 1777

engraving, ink on paper

28.2 x 49.2 cm

Collection of Flinders University Museum of Art 1601

Between 1772 and 1775 William Hodges accompanied James Cook to the Pacific as the expedition's artist. Many of his sketches and wash paintings were adapted as engravings for the original published edition of Cook's journals from the voyage. This work, adapted by John Keyse Sherwin, recounts Cook’s landing on the island of Eua in the kingdom of Tonga. Eua was first put on European maps by Abel Tasman (1603-1659) who reached its shores in 1643 and named it Middelburg Island after the capital of the Dutch province of Zeeland.

In Cook’s publication the notes accompanying the etching describe the scene as follows:

Cook standing in a small rowing boat leaning on this gun with the Tongan chieftain Tionee in front of him, holding up a plantain leaf, approaching the shore of Eua, where men, women and children are gathered, offering armloads of fruit to barter, with a thatched building under trees, on a hill to the right, with small rocks and bushes in the right foreground.1

Sherwin’s work is particularly striking for its portrayal of Eua men and women who bear the appearance of classical statues evinced by the clear definition of their forms and staged figuration. Associated with visual language first established by the Ancient Greeks and Romans to express ideas of logic, rationalism and moral order, here the so-called neoclassical style plays into the ‘noble-savage’ concept – a notion widely attributed to Swiss philosopher Jean Jacques Rousseau (1712-1778), which perceived an innocence, purity and authenticity in peoples that lived free of the corrupting influence of modern civilisation. The idea of ‘noble-savage’ is intertwined with the history of imperialism and colonialism, and Enlightenment theories where false hierarchies of race constructed people of colour as inferior to white Europeans.

1 J Cook, A voyage towards the South Pole, and round the world: performed in His Majesty’s ships the Resolution and Adventure, in the years 1772, 1773, 1774 and 1775, W Strahan and T Cadell, London, 1777, p192.

2

Robert Cleveley

born 1747, Deptford, England

died 1809, Dover, England

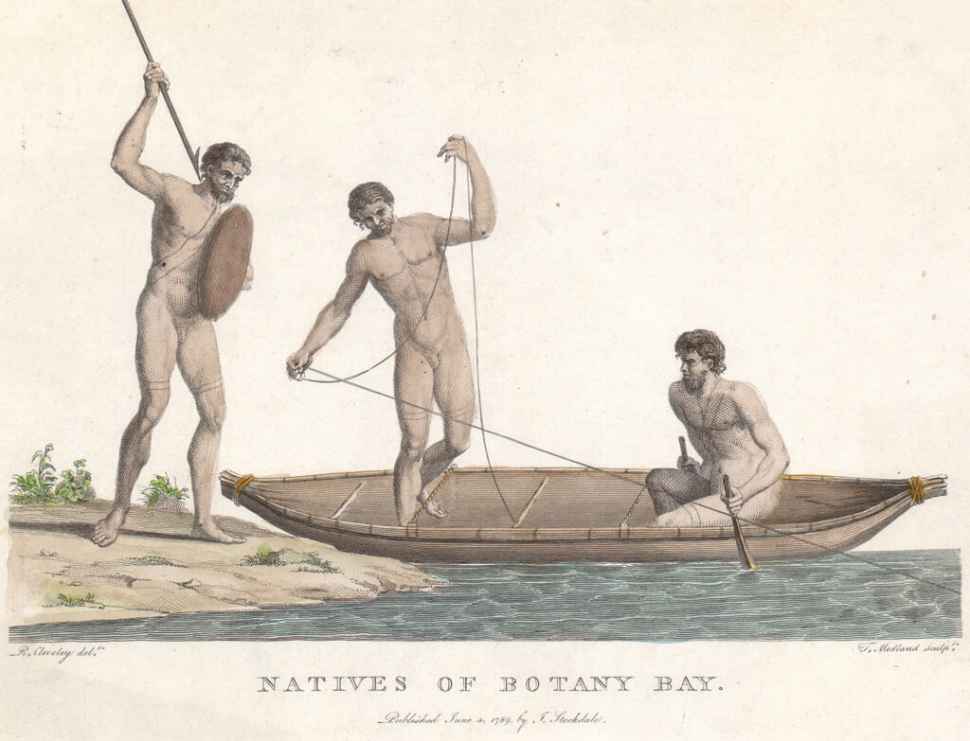

Natives of Botany Bay 1789

hand-finished lithograph, coloured inks on paper

18.9 x 28.2 cm, plate 5

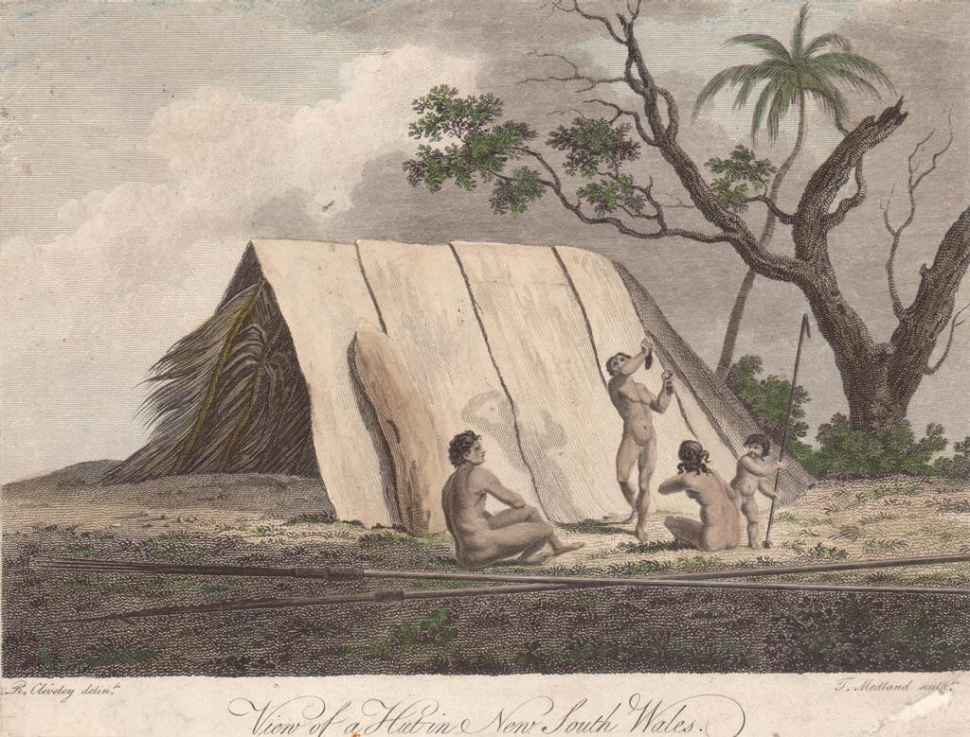

View of a hut in New South Wales 1789

hand-finished lithograph, coloured inks on paper

21 x 27.2 cm, plate 8

Gift of Cate Jones

Collection of Flinders University Museum of Art 5793

Collection of Flinders University Museum of Art 5794

In 1787, the British Empire sent the ‘First Fleet’ of ships carrying convicts to Australia under the command of Captain Arthur Phillip (1738-1814). Landing at Botany Bay on 26 January 1788, Phillip founded a penal colony at Sydney Cove, Port Jackson, and was made Governor of New South Wales. These coloured illustrations accompany Phillip’s account of the journey and settlement including observations of Aboriginal people. The book, entitled The Voyage of Governor Phillip to Botany Bay, was published by John Stockdale (1750-1814) in London in 1789.

The scenes portrayed in these works are romanticised and illusory, yet they are composed in ways that make them appear ageless and objective, an effect achieved through clarity of form, sober colours, shallow space and strong horizontals and verticals. In their day, visual representations of this kind – that were ‘scientific’ in their look and feel – were taken as ‘proof’ of the advanced state of Western civilisation and instrumentalised to maintain and promulgate British ideologies of race.

3

Unknown artist

The bush scene in the South Australian court c.1880

hand-finished wood engraving, coloured inks on paper

30.5 x 35.5 cm

Gift of Ali Gumillya Baker

Collection of Flinders University Museum of Art 5792

Presented in The Australasian Sketcher (1873-1889), a monthly magazine published by The Argus in Melbourne, this illustration provides a view of the 'Bush Scene' diorama that was constructed in the South Australian Court for the Melbourne International Exhibition held in the Carlton Gardens Exhibition Buildings between 1 October 1880 and 30 April 1881. The image was accompanied by the following description:

Mr. Davenport has devised a "bush scene," grouping together the most characteristic features of aboriginal life […] a blackfellow has brought home a wallaby which he has just speared, and his lubra, with her picaninny, is surveying the promised supper from the inside of a wurley. A distant mountain-scene is painted on the walls, and thanks probably to the executive commissioner having himself been a pioneer, every detail of the scene is carried out with a faithfulness to which none but an old bushman can do justice. To European visitors this peep into bush-life will be most interesting, and judging by the crowds which are constantly gathered a-round, everybody is grateful to the South Australians for making such a country oasis amidst the desert of civilisation.

From the late 19th century dioramas were commonplace at world fairs, their themes and forms appearing across settler colonies and imperial nations. In some instances, living people were embedded in the scenes and inhabited the displays for months on end. Dioramas of non-European peoples also appeared at this time in museums. Presented as ahistorical and static, these were organised within ‘natural history’ exhibits according to Western classifications of culture and the supposed inevitability of racial demise according to false Social Darwinist hierarchies of ‘survival of the fittest’. By positioning human subjects within a zoological tableau, the diorama – more than any other mode of colonial representation – activated binaries about primitive/civilised cultures and associated subtexts that served the social and political interests of the colonisers.

1 ‘The courts’, in The Australasian Sketcher with Pen and Pencil, 23 October, 1880, p278.

4

Christian Thompson

born 1978, Gawler, South Australia

Bidjara people

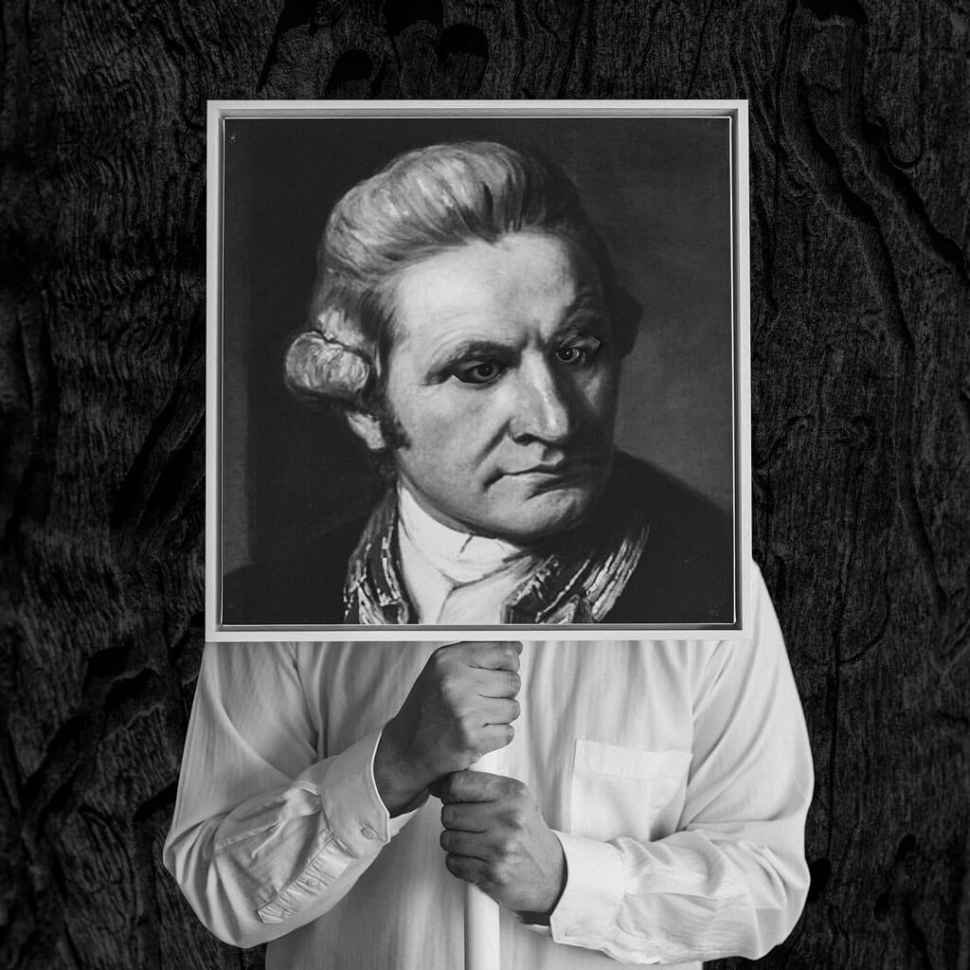

Museum of Others (Othering the Explorer, James Cook)

from the series Museum of Others 2016

c-type photograph on metallic paper

120 x 120 cm

Collection of Flinders University Museum of Art 5808

© Christian Thompson / Courtesy Michael Reid Sydney + Berlin 2020

Born in South Australia, Thompson travelled extensively with his family while growing up, but considers his home to be in South West Queensland, on the lands of his Bidjara ancestors. He graduated from the University of Southern Queensland with a Bachelor of Visual Arts (Fine Arts) in 1996 before undertaking postgraduate study at the Royal Melbourne Institute of Technology in 2004 and Dasarts, The Netherlands in 2008. In 2010 Thompson made history when he became the first Aboriginal Australian to be admitted into the University of Oxford in its 900-year history. He graduated with a Doctor of Philosophy in 2015. A multidisciplinary artist working in photography, video, sculpture, performance and sound, Thompson’s practice engages with themes of identity, sexuality, gender, race and memory.

Museum of Others (2016), is part of the artist’s conceptual practice that explores how historical collections can become active forces in the production of contemporary cultural expression. The work emerged from his research at the Pitt Rivers Museum during his Doctoral studies and comprises a series of large format photographs featuring notable British colonial figures – here Captain James Cook, in other works John Ruskin (1819-1900), Augustus Pitt Rivers (1827-1900) and Sir Walter Baldwin Spencer (1860-1929). Barely perceptible, the eyes of each figure have been meticulously removed to reveal the artist’s own, a strategy enabling Thompson to return a new gaze from within the historical subject, opening the past to view an entirely different present.

In their pursuits, these colonial figures were actively ‘Othering’ Indigenous peoples, as evidenced in this extract from Cook’s log book:

[…] they may appear to some to be the most wretched people upon Earth, but in reality they are far more happier than we Europeans; being wholy unacquainted not only with the superfluous but the necessary conveniencies so much sought after in Europe, they are happy in not knowing the use of them.

In this text, Cook objectifies and romanticises Indigenous peoples, promulgating the myth of the ‘noble-savage’, the idealised and imperialist concept of the ‘uncivilised’, that persists in contemporary society today. Thompson counters this construct by inverting the gaze and ‘Othering’ Cook himself.

1 J Cook, Journal of HMS Endeavour, 1768-1771, manuscript, National Library of Australia website, accessed Tuesday 26 May, <https://www.nla.gov.au/digital-classroom/senior/Cook/Indigenous-Response/Endeavour-Journal>.

5

Micky Allan

born 1944, Melbourne, Victoria

Larry Rawling (printer)

born 1938, Melbourne, Victoria

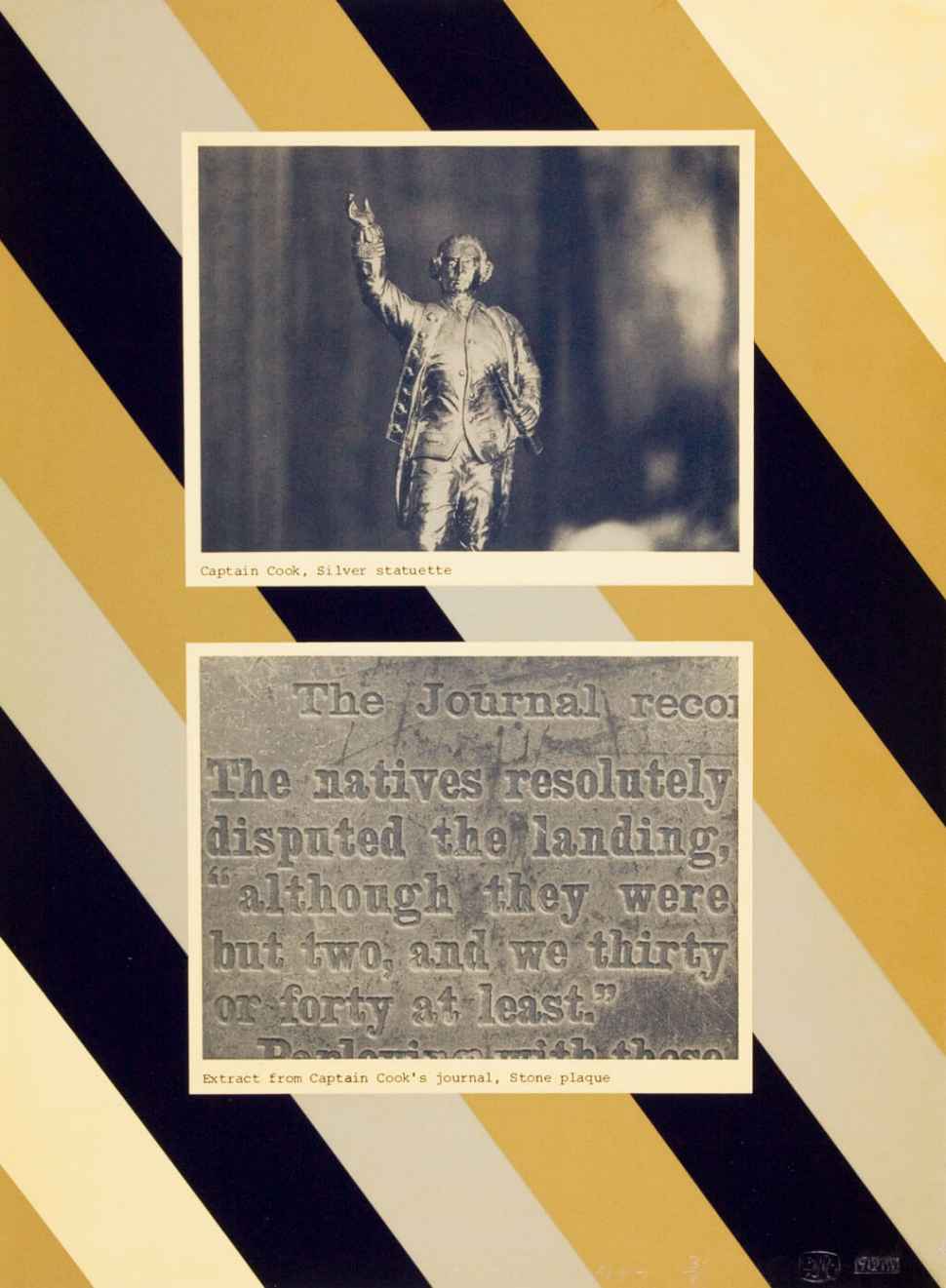

Untitled 1987

screenprint and photoscreenprint, coloured inks on paper

76 x 56.5 cm, ed. 31/80

Collection of Flinders University Museum of Art 2566.001

© Micky Allan / Copyright Agency 2020

Australian photographer and painter Micky Allan created the print Untitled (1987), in response to the 1988 bicentenary of European settlement which celebrated the invasion of Aboriginal land. The artist was commissioned, as one of 25 artists, by the National Gallery of Australia with funds from the Australian Bicentennial Authority, to produce a limited edition at the Victorian Print Workshop for The Bicentennial Folio: prints by twenty-five Australian artists (1988).

In the print, Allan reproduces two photographs from her earlier series Botany Bay Today (1980), which catalogue the degeneration, industrialisation and pollution of the coast since its colonial occupation in 1788. The monochrome images in Untitled, depict a statue of James Cook, marking his invasion of Dharawal Country and ‘discovery’ of Botany Bay on 29 April 1770, and the associated plaque cropped to highlight the inscription, ‘The natives resolutely disputed the landing, “although they were but two, and we thirty or forty at least.”’. The text, an extract from Cook’s journal, amplified in Allan’s photoscreenprint, affirms the land as occupied by Indigenous peoples and contests the claim of terra nullius. These documentary style images sit against a background of diagonal stripes. Here, the artist references a school tie which alludes to ‘boys’ club’ culture and brings to attention the patriarchal and privileged nature of the colonial endeavour.

6

Therese Ritchie

born 1961, Newcastle, New South Wales

They all look the same to me 2020

inkjet print on archival paper

50 x 80 cm, artist’s proof

Collection of Flinders University Museum of Art TAN 1907

© Therese Ritchie 2020

Therese Ritchie is a prolific Darwin-based non-Indigenous artist who utilises her extensive skills in photography and graphic design to produce works that make hard-hitting social and political comment on Australian society, particularly in regard to Indigenous rights.

In They all look the same to me (2020), Ritchie appropriates and digitally manipulates Francis Wheatley’s (1747-1801) sentimental realist painting of the Royal Navy officer, Vice-Admiral Arthur Phillip (1738-1814). The English artist painted Arthur Phillip (1786), shortly after the officer’s appointment as Governor of New South Wales, before he set sail on 13 May 1787 for Dharawal Country, Botany Bay. In anticipation, the work romanticises and commemorates ‘heroic’ colonial conquest, which is symbolised by the depiction of Phillip striding ashore.

In Ritchie’s version, the silhouette of Phillip is invaded by a virus enlarged under electron microscopical view, that colonises and multiplies inside his body. Infected and recast as the villain, he carries the devastation of imperialism like a disease to the Australian continent, instantly contaminating codfish (a useful food source), that lie dead on a rock beside him. Ritchie reduces Phillip’s identity to a shadow, revealing the peripheral items of a typical British captain’s uniform: hat, wig and shoes with brass buckles, which act as identifiers for an unwanted, unnamed explorer. Made in response to the 250th anniversary of Captain Cook’s voyage to Australia and the Pacific in 1770 and in the context of the global 2020 coronavirus pandemic, Ritchie redirects the racist slur, ‘They all look the same to me’, towards the fleet of colonial explorers.

7

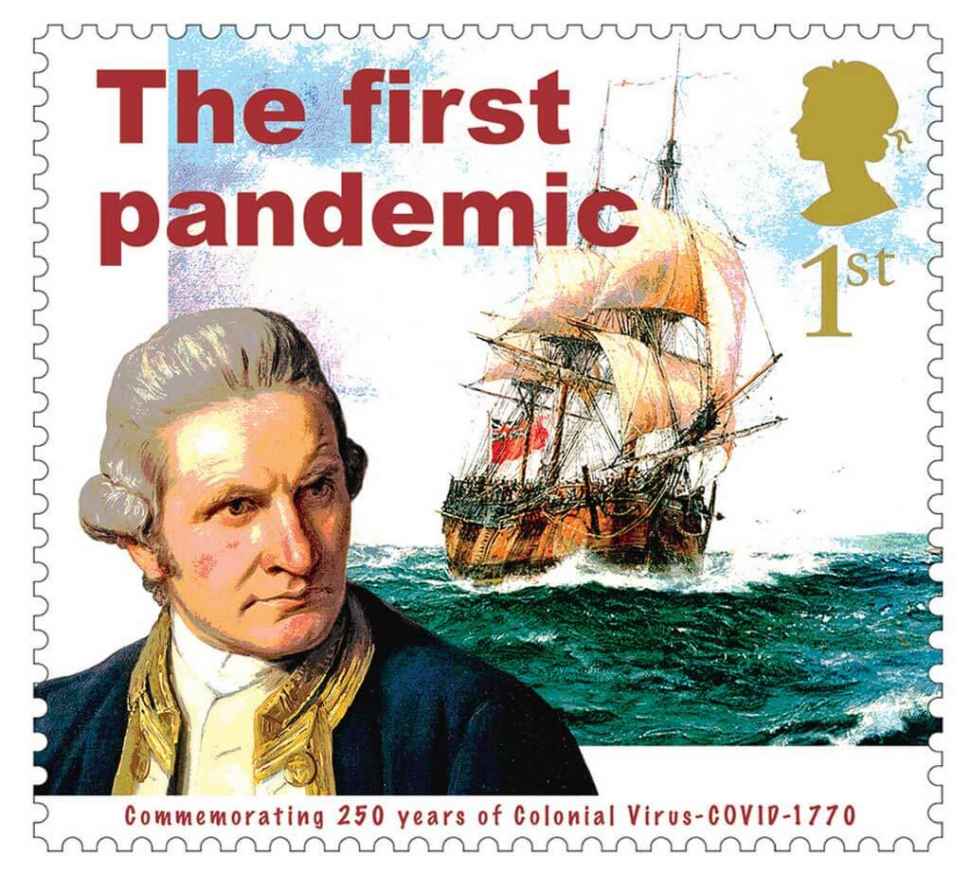

Chips Mackinolty

born 1954, Morwell, Victoria

The first pandemic 2020

digital print on archival paper

40 x 36 cm, ed. 12/19

On loan from private collection

© Chips Mackinolty 2020

Chips Mackinolty is a graphic artist, activist, journalist and scholar based in Alice Springs where he is currently Executive Director, Researcherenye Wappayalawangka, Central Australia Academic Health Science Network. A former member of the Earthworks Poster Collective, Tin Sheds, University of Sydney (1974-79), he produced his first political poster as a student in 1969 calling fellow students to action in protests over the Vietnam war. Since then Mackinolty, who moved to the Northern Territory in 1981, has created a vast body of politically motivated work, shifting over this period, from screen to digital printing processes.

The first pandemic, created at the height of concerns about the spread of COVID-19 in Australia in early 2020, takes aim at Cook and ensuing British boats originally responsible for bringing novel and deadly diseases to the continent. As early as 1789, just 15 months after the arrival of the First Fleet, smallpox spread into Aboriginal communities in Sydney Cove and Botany Bay with records indicating that it resulted in the death of 70% of those infected. With the advance of European settlement smallpox spread deeper into the country devasting entire generations of Aboriginal people and destroying some communities entirely.

The spread of smallpox was followed by influenza, measles and tuberculosis, all of which Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples had no resistance to, and all of which brought widespread death. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities remain most vulnerable to disease - including COVID-19 - due to a range of factors determining health outcomes, most significantly the impact of colonial ideas of race that persist in the current day.

8

Ali Gumillya Baker

born 1975, Rose Park, South Australia

Mirning people

Tall ships part 1 2014

video, duration 46 sec

Tall ships part 2 2014

video, duration 34 sec

The colonial imagination/down among the wild men 2014

video, duration 26 sec

Sovereign Fleet (black) 2013

featuring Alexis West (performer)

photographic print on archival paper

157.5 x 107 cm

On loan from the artist

© Ali Gumillya Baker 2020

Ali Gumillya Baker is a Mirning woman from the Nullarbor on the West Coast of South Australia who is a multidisciplinary artist and educator. She completed a Bachelor of Visual Arts (Honours) at the University of South Australia in 1997 and Master of Arts in Screen Studies at Flinders University in 2002. In 2018 she was awarded a Doctor of Philosophy in Cultural Studies and Creative Arts from the same institution. Currently employed as a Senior Lecturer in the College of Humanities, Arts and Social Sciences at Flinders University, Baker’s research interests are colonial archives, memory and the intergenerational transmission of knowledge. As well as working as an independent artist, Baker is a member of the Unbound Collective which was formed in 2014 with colleagues Faye Rosas Blanch, Natalie Harkin and Simone Ulalka Tur.

In 1988, when Baker was 12, she travelled to Sydney with her family to join more than 40,000 people who converged on the city to protest over the nation’s 200 year bicentennial celebrations. These events focused on the idea of European discovery and featured a re-enactment of the arrival of the First Fleet. Baker’s ‘tall ship’ works recall this performance and explore the enduring symbolism of these vessels for this country’s First Nations peoples today. In Sovereign Fleet (2013), Baker draws inspiration from 18th century French fashion which briefly saw elaborate millinery featuring tall ships in sail. These hats were worn patriotically as a sign of anti-British sentiment following the Battle of Ushant in 1778, in which the French frigate Belle Poule, badly damaged a British boat. In Baker’s work, the recreation and repositioning of the tall ship within the discourse of Australian colonial history is a critical and creative strategy that explores the idea of how sovereignty is performed.

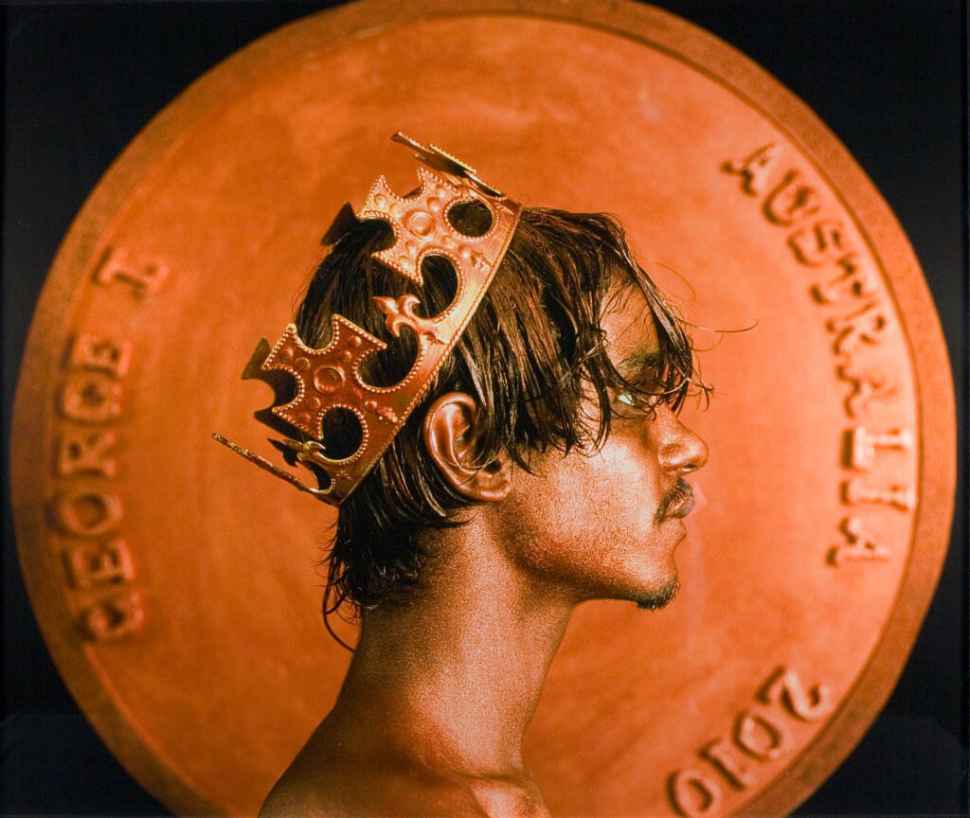

9

Darren Siwes

born 1968, Adelaide, South Australia

Dalabon people

Bronze boy 2007

from the series Oz Omnium Rex Et Regina

cibachrome photographic print on metallic paper

107.5 x 127 cm, ed. 4/10

Collection of Flinders University Museum of Art 4467.001

© Darren Siwes 2020

Darren Siwes is an artist and educator. He is the son of a Dutch father and Dalabon mother with ties to Country in southern Arnhem Land. Siwes completed a Bachelor of Visual Arts (Honours) in 1996 and Graduate Diploma of Education in 1997 at the University of South Australia; and Master of Arts at the Chelsea School of Art, London, in 2003. A self-described ‘hypothetical realist’, his photographic practice blurs the boundaries between ‘true’ and imagined worlds to interrogate colonial narratives, cultural stereotypes and racial hierarchies.

Bronze Boy (2007), is from the series Oz Omnium Rex Et Regina, in which Siwes contemplates the possibility of an Indigenous head of state by featuring Aboriginal people on yet to-be-minted Australian coins. In these works, the artist explores the symbolism of the coin itself as a cipher of political expression – of sovereignty and national identity – while also examining ideas of value and power rooted in ideologies of class and race. The profile of the young Aboriginal man depicted in this work has the air of a regal figure, yet the face captured in this way could equally be a mugshot or contemporary iteration of the so-called ‘noble-savage’. By playing with social expectations and internalised norms that shape perceptions of the world, Siwes disrupts powerful and deeply entrenched stereotypical thinking about Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and their contemporary identities.

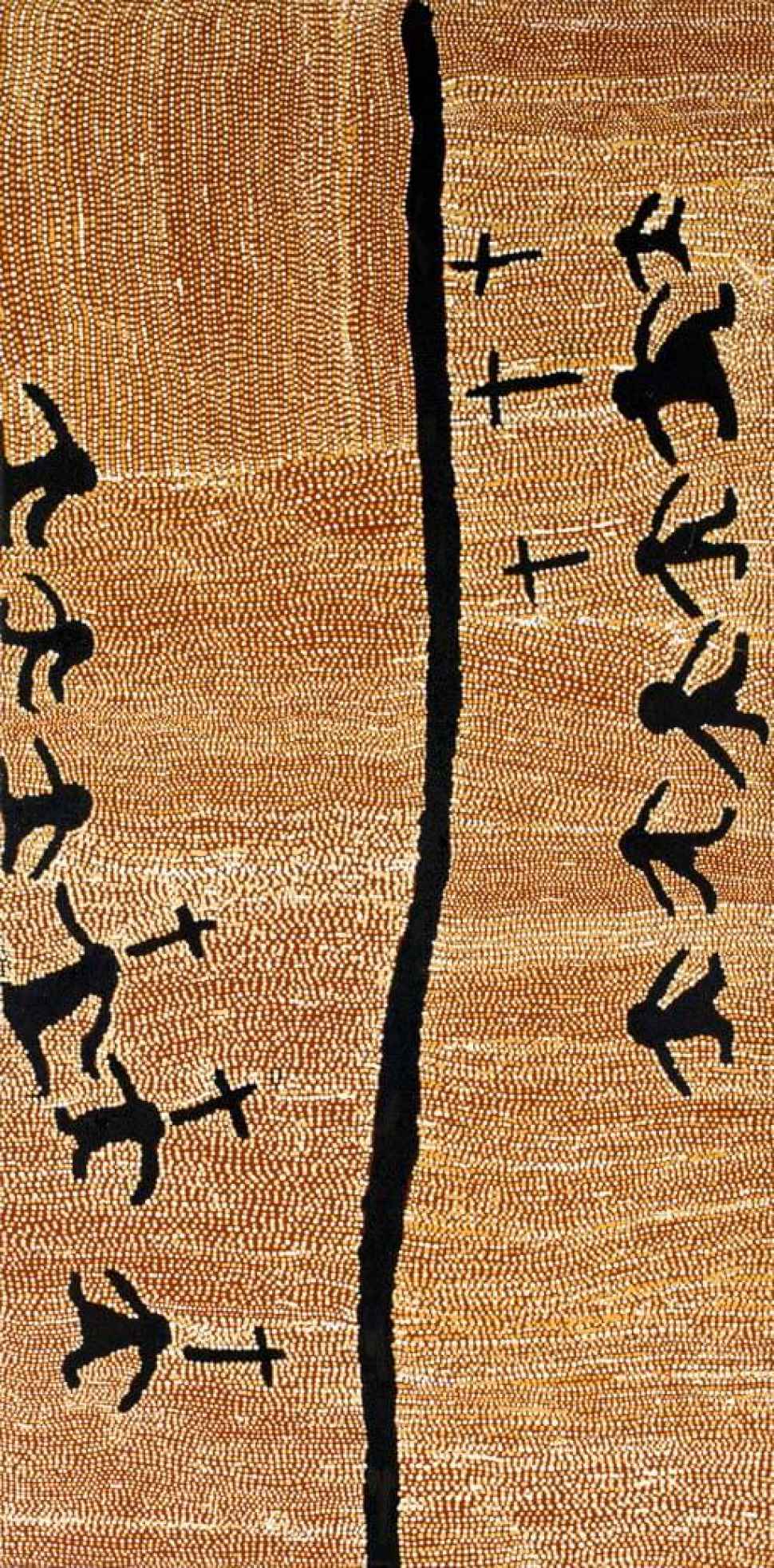

10

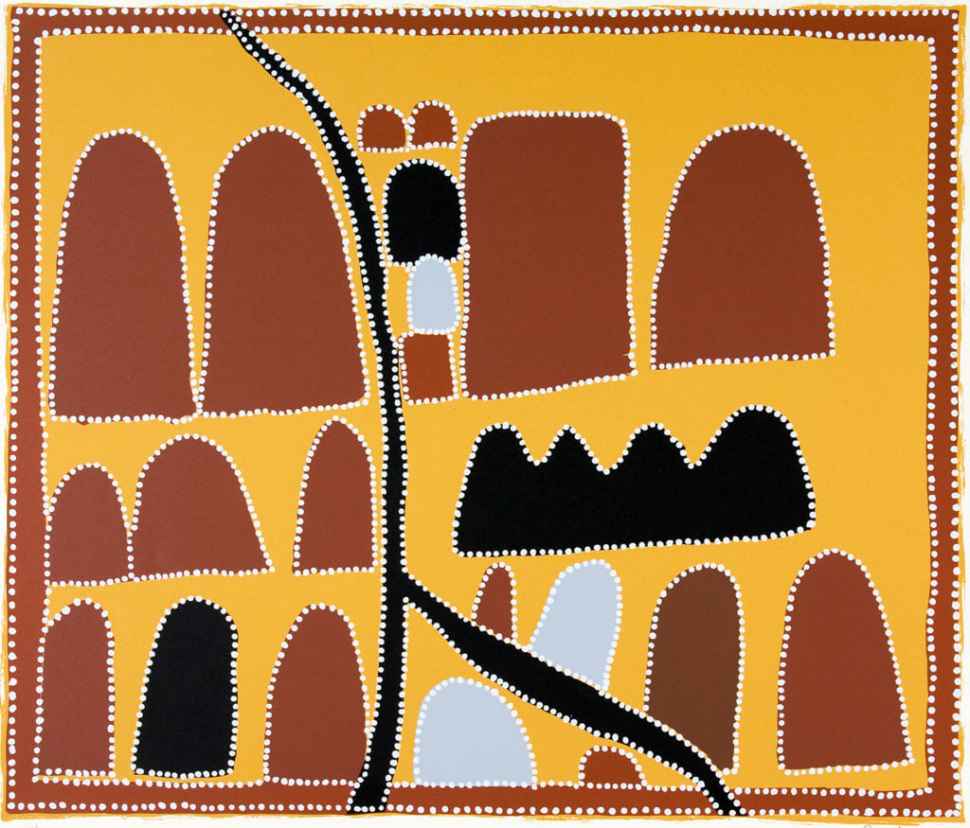

Wentja Napaltjarri 2

born 1945, Malparinga, Western Australia

Pintupi and Luritja peoples

First contact: missionaries at Haasts Bluff 2003

synthetic polymer paint on canvas

122 x 60.5 cm

Collection of Flinders University Museum of Art 3943

© Wentja Napaltjarri 2 / Copyright Agency 2020

Senior Pintupi/Loritja artist Wentja Napaltjarri 2 is best known for painting her father, Shorty Lungkata Tjungurrayi’s Country, west of Kintore in the Gibson Desert, and influenced by the rhythmical Western Desert mark-making style that her father co-established in the early 1970s. Her oeuvre is informed by her father’s teachings in Tjukurrpa (Ancestral Stories) and her early childhood travels from her birthplace of Malparinga, a rockhole near the south-west of Lake Mackay, Western Australia, to Ikuntji (Haasts Bluff), in Central Australia, 50 kilometres west of Hermannsburg and 230 kilometres west of Alice Springs.

At Ikuntji, the Haasts Bluff Native Settlement was established in 1941 as a government ration depot and a means for gathering and controlling Aboriginal peoples under ‘Protection’ policies implemented nationally as part of Social Darwinist ideologies, and during the severe drought that spanned 1937-1945. This hardship was intensified for First Nations peoples by the desecration of their land and loss of their food sources due to the growing cattle industry. Missionaries from the Lutheran Mission at Ntaria (Hermannsburg), were subsidised by the government to provide welfare services at the Ikuntji settlement. Napaltjarri’s work First contact: missionaries at Haasts Bluff (2003) is a sensitively rendered yet direct painting that documents the artist’s earliest exposure to missionaries and Christianity, as well as her first contact with non-Indigenous people, at the young age of about three years old, when she and her family arrived at Ikuntji in 1948. In the work, divided by a black sweeping band, possibly representing one of the creeks in the region, Napaltjarri depicts small and large figures silhouetted against the shimmering, sandy desert-country of Ikuntji. Black crosses hover nearby, referencing the anonymous missionaries and their religion that has impacted Indigenous people since colonisation.

11

Fiona Foley

born 1964, Maryborough, Queensland

Badtjala people

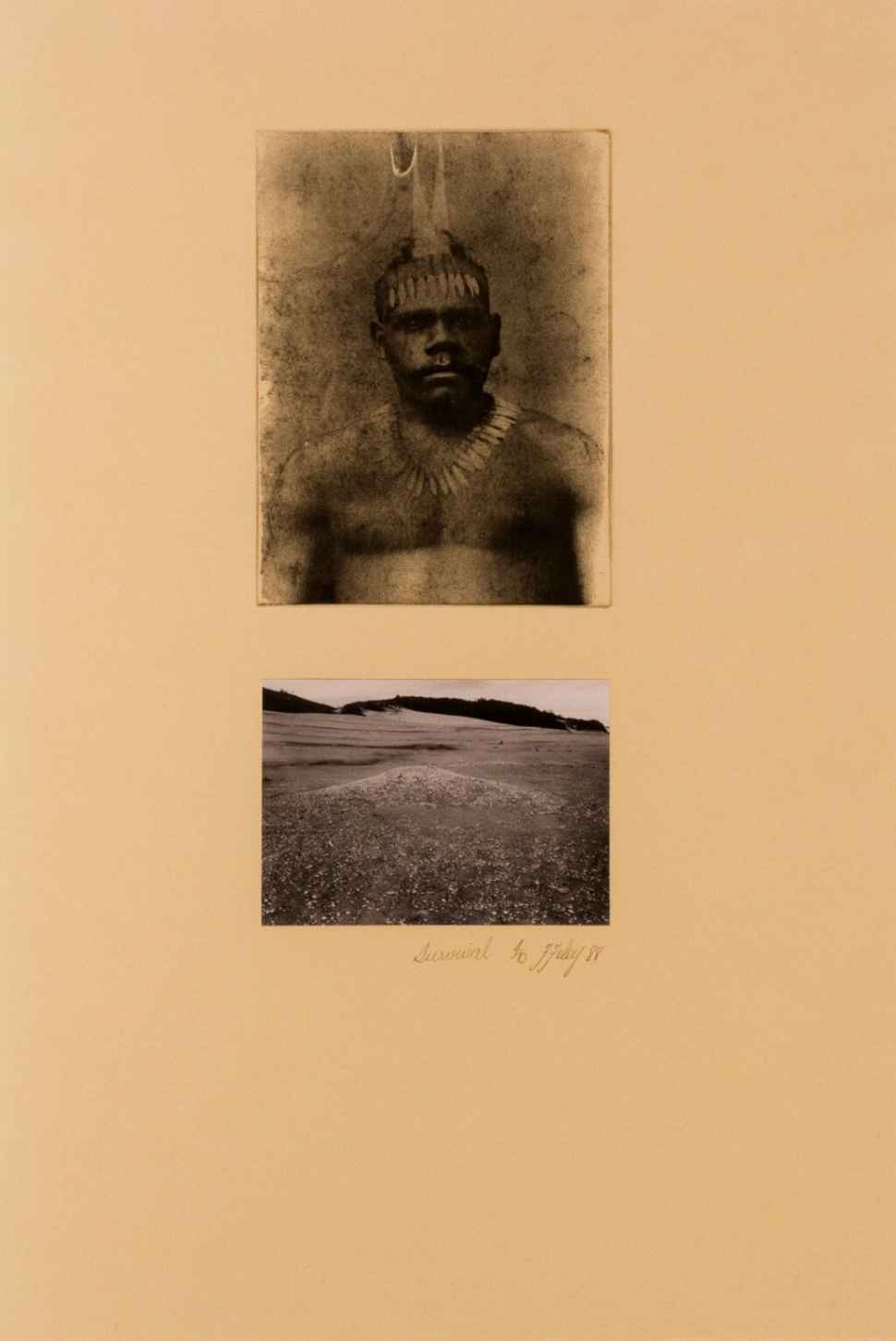

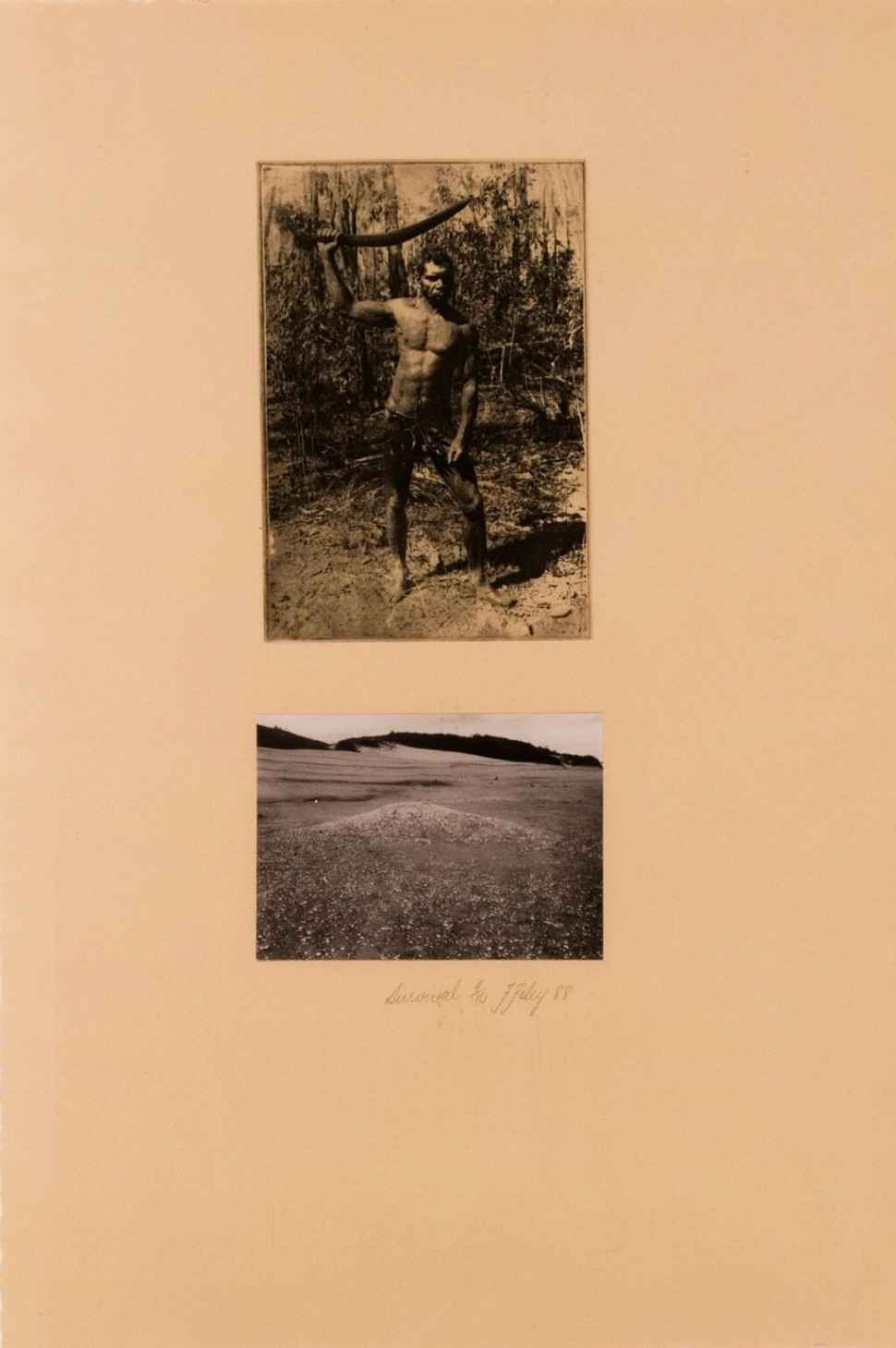

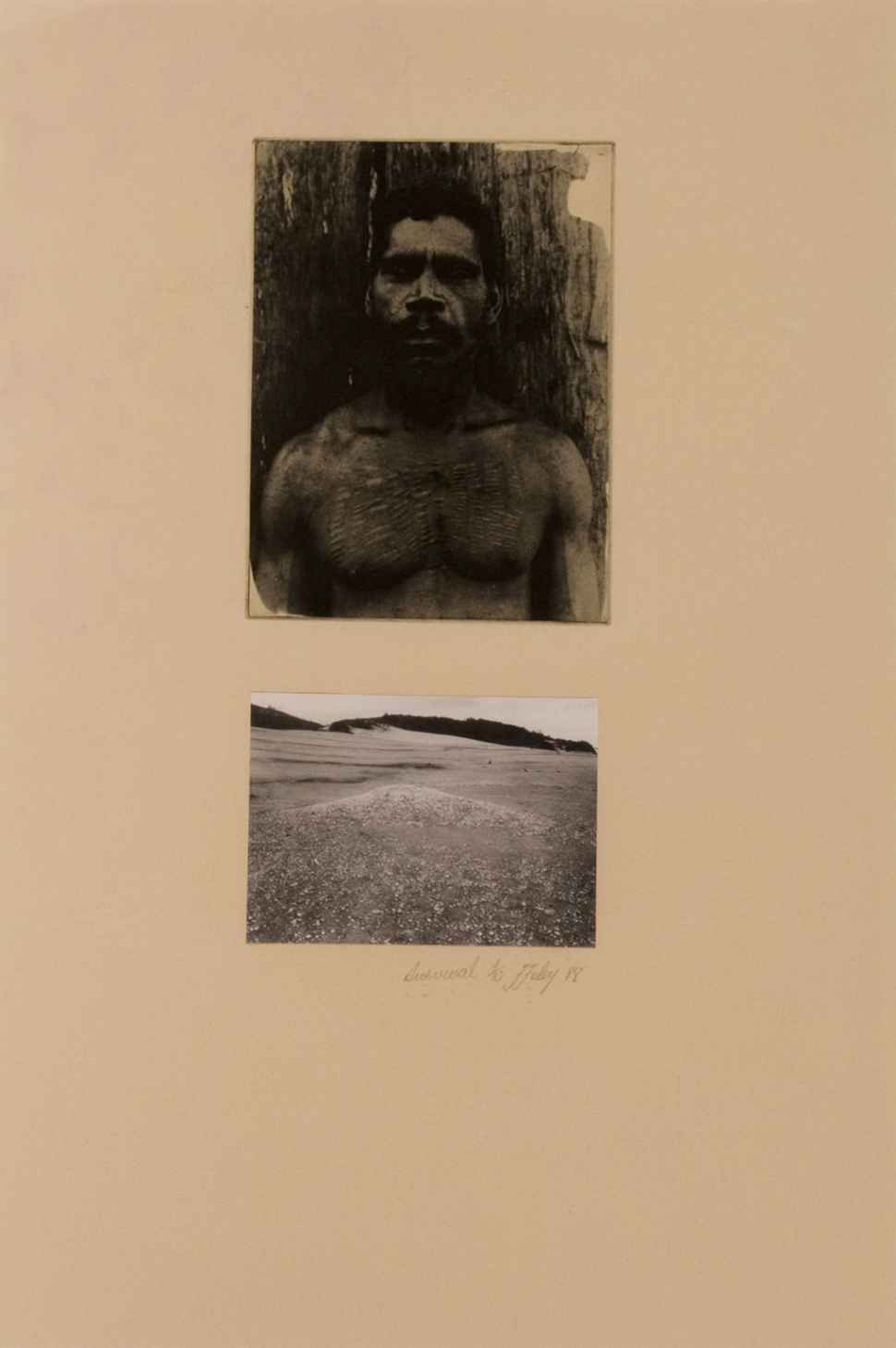

Survival 1988

photoengraving and collage on paper

56.5 x 38 cm (each), ed. 4/10

Collection of Flinders University Museum of Art 2872.002 – 004

© Fiona Foley 2020

Fiona Foley is an artist, curator, writer and academic who was born to a Badtjala mother and Irish-Australian father. Her earliest years were spent in Hervey Bay on the Fraser Coast Region of Queensland before moving with her family to Mount Isa and then Sydney. She was awarded a Bachelor of Visual Art from the University of Sydney in 1986. The following year she completed a Diploma of Education at the same institution and co-founded the Boomalli Aboriginal Artists Co-operative alongside nine other prominent Indigenous artists. In 2017 Foley was awarded Doctor of Philosophy by Griffith University and appointed Adjunct Professor to Gnibi College of Indigenous Australian Peoples at Southern Cross University. The artist’s multidisciplinary arts practice encompasses installation, photography, printmaking, sculpture, and film as a means to grapple with Aboriginal history, identity and sovereignty through the lens of her experience as a Badtjala woman.

Foley created the Survival series in 1988, the year of the Australian Bicentenary in which she made a speech mourning the loss of her Badtjala ancestors from K’gari (Fraser Island). In honouring and bearing witness to their history and memory in this work, she reproduced images from the public record that evidence Badtjala presence on the island in colonial and pre-colonial times. These include 19th century photographic portraits from the archives of the John Oxley Library, Queensland featuring Badtjala leaders, among them Foley’s great-great-grandfather, and a picture postcard of K’gari discovered by Foley in a Brisbane shop. Featuring a shell midden, the postcard verifies the long-standing presence of her people at this coastal site. Nine years after the creation of Survival, Foley joined her mother in lodging a native title claim on K’gari on behalf of the Badtjala people, which was awarded in their favour in 2014.

In her most recent project – Out of the Sea Like Cloud (2019) – Foley produced a film that sheds light on Cook’s passage along the K’gari shoreline on 20 May 1770, from the perspective of her Badtjala ancestors who recorded the event in song. Taking its title from a surviving English translation of the song’s opening line, Foley reflects on knowledge that has been handed down over generations of Badtjala oral history which is believed to be the oldest recorded Aboriginal observation of Cook.

12

Queenie McKenzie

born 1915, Texas Downs, Western Australia

died 1998, Warmun, Western Australia

Gija people

Osmond Creek (Dadah aw Ning) 1996

screenprint, coloured inks on paper

62 x 71 cm, ed. 43/50

Collection of Flinders University Museum of Art 3205

© the Estate of Queenie McKenzie 2020

Gija painter Queenie McKenzie was born at Texas Downs Station in the north-eastern reaches of Western Australia to a Malngin/Gurindji mother and European father. As a young girl with fair skin growing up under the nation’s assimilationist policy, she evaded being taken away from her family on multiple occasions. McKenzie worked as a cook on cattle stations across the region for much of her life before settling at Warmun (Turkey Creek) in 1973, where she became a leader in Gija women’s law and ceremony. In 1987, with the encouragement of Rover Thomas (1926-1998), McKenzie became the first female painter in her community. Her earliest prints were made in 1995 in collaboration with printmaker Theo Tremblay (1952-).

This abstract image recalls the plight of an Aboriginal boy killed by policemen for his alleged hand in the death of two non-Indigenous men speared whilst mustering cattle. It is understood that following the crime, the boy fled through surrounding areas such as Tabletop Mountain and Nine Mile bore, in central Western Australia, pursued by police officers who eventually captured and beheaded him. Unlike the Coniston Massacre in 1928, which was documented in official records, the only known traces of the incident referenced by McKenzie are found in Gija paintings and oral histories.

13

Lin Onus

born 1948, Melbourne, Victoria

died 1996, Melbourne, Victoria

Yorta Yorta people

Dislocation 1986

linocut, ink on paper

29.6 x 20.7 cm, ed. 7/9

Collection of Flinders University Museum of Art 2300

© Lin Onus Estate / Copyright Agency, 2020

Yorta Yorta artist and activist Lin Onus is considered a seminal painter and sculptor, influencing the breadth and direction of contemporary Aboriginal art as it unfolded in the 1980s and 1990s. Over his 30-year career as a self-taught and self-determined Melbourne-based artist with a Yorta Yorta father and a Scottish mother, Onus explored the complexities of his Aboriginal and European ancestry.

A turning point in the artist’s career was meeting Djinang elder and artist Jack Wunuwun in Maningrida in 1986. Wunuwun was to become Onus’ adopted father and mentor, gifting him cultural knowledge and visual iconography which Onus subsequently used to create his signature style that merged photo-realism with Aboriginal motifs, particularly rarrk (Arnhem Land crosshatching).

In the same year, Onus created a one-off series of prints, including the linocut Dislocation (1986), which he states is, ‘about the effect on children as they, their brothers and sisters, and parents were moved about and families were split up’.1 In the work, rightful innocence, symbolised by the image of a child clutching sprigs of flowers whilst confronting the viewer, is fractured into 10 shards against a rarrk-like background. Here, Onus presents a stark image of disrupted identity and sense of belonging, and in doing so, gives voice to experiences of fragmentation and alienation for many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples since the invasion of this country 250 years ago.

1 L Onus, personal correspondence with JVS Megaw, 26 July 1986, Flinders University Museum of Art archive file 2300.

14

Richard Bell

born 1953, Charleville, Queensland

Kamilaroi, Kooma, Jiman and Gurang Gurang peoples

We’re not (French)

We’re not (German)

We’re not (Japanese)

from the series We’re not 1993

synthetic polymer paint and paper on canvas

30 x 23 cm (each)

Collection of Flinders University Museum of Art 3050, 3051, 3052

© Richard Bell / Courtesy Milani Gallery, Brisbane 2020

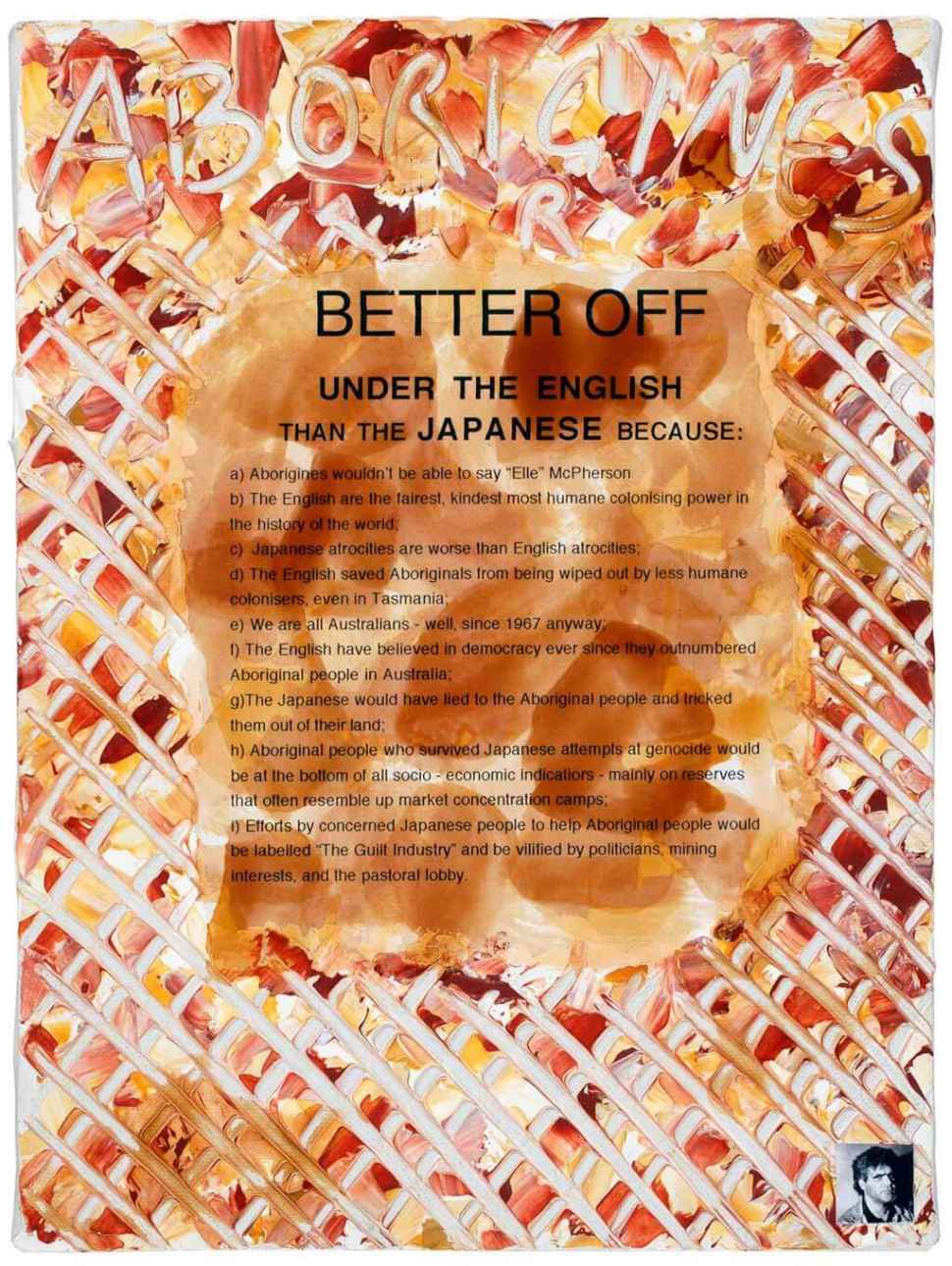

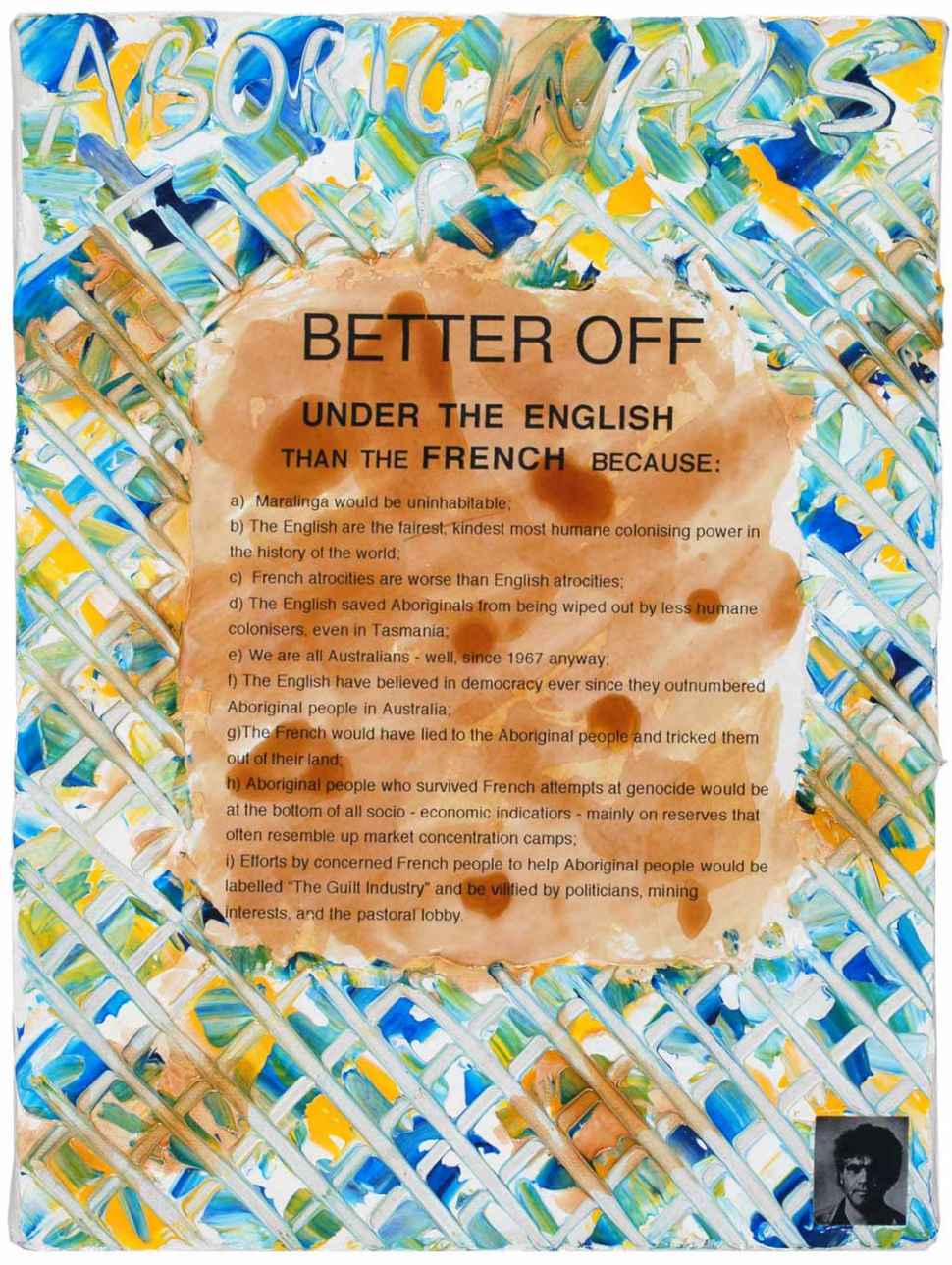

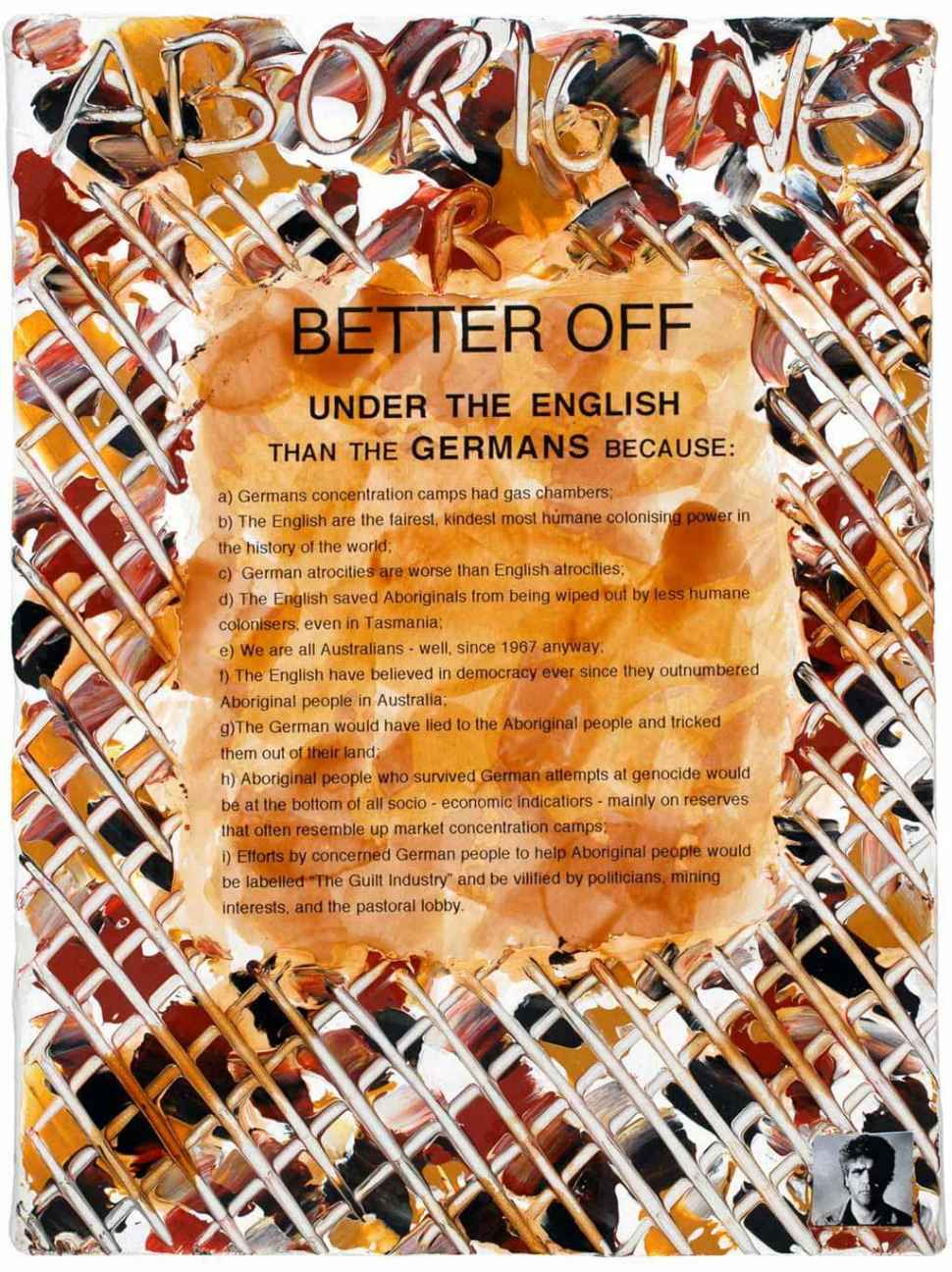

Self-taught multidisciplinary artist Richard Bell utilises the mediums of painting, text, installation, performance and video as a platform to drive his unflinching activism to an international audience. He manufactures works of protest, employing humour as a tool to attack and invert mainstream ideas about Indigenous and non-Indigenous relations in Australia. He says, ‘...the reason I make art is to tell what I reckon are the important stories and significant events that have happened during my lifetime in the hope that they would be recorded and exhibited...so that white Australia can’t just rewrite our history again.’.1

Bell’s early series, We’re not (1993), is an example of his ability to undercut racial stereotypes and colonial mythologies that persist in contemporary Australia. The expressive paintings pivot on the racist phrase, ‘Aborigines are better off...’, which dominates imperious discourse prevalent in Australian politics, media and backyards. The triptych is also a sardonic play on the rationalisaton of the colonial enterprise and present-day Australian government policymaking.

We’re not, is an ironic proclamation presented on discoloured paper, suggestive of archived colonial documents such as Governor Bourke’s (1777-1855) proclamation of terra nullius in 1835 or Governor Arthur’s (1784-1854) Proclamation to the Aborigines (1828-1830). The inscriptions are postered against a scratch-graffiti pattern of chain-wire fence, echoing the enclosures used in early to mid-nineteenth century settlements and compounds ‘designated’ for displaced First Nations people, which still mark many communities today. The series, authorised with the stamp of a photographic self-portrait of the artist, is a satirical reference to the ‘humane’ colonisation of Australia; Aboriginal citizenship; genocide of Indigenous peoples; and the British nuclear tests on Anangu Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara Lands at Maralinga, South Australia between 1952-1963.

1 ‘Richard Bell wins the Australia Council Visual Arts Award’, Art Almanac website, accessed 21 May 2020, <https://www.art-almanac.com.au/richard-bell-wins-the-australia-council-visual-arts-award/>.

15

Ryan Presley

born 1987, Alice Springs, Northern Territory

Marri Ngarr people

One Hundred Dollar Note – Gladys Tybingoompa Commemorative

Fifty Dollar Note – Fanny Balbuk Commemorative

Twenty Dollar Note – Woloa Commemorative

Twenty Dollar Note – Jandamarra Commemorative

Ten Dollar Note – Oodgeroo Commemorative

Ten Dollar Note – Vincent Lingiari Commemorative

from the series Blood Money 2014

digital print on adhesive

45.3 x 15.5 cm (framed)

On loan from private collection

© Ryan Presley / Copyright Agency 2020

Born in Alice Springs Ryan Presley lives and works in Brisbane. Through his father he is connected to the Marri Ngarr people of the Moyle River region in the Northern Territory. His mother’s family emigrated to Australia from Scandinavia. Presley completed a Doctor of Philosophy at the Queensland College of Art, Griffith University, in 2016 following an honours degree in contemporary Australian Indigenous art undertaken at the same institution. The artist’s multidisciplinary practice encompasses diverse mediums and techniques, chief among them drawing, etching and painting.

Blood Money (2010-) is an ongoing project concerned with the intersections of colonialism and currency, and the honouring of Aboriginal resistance to encroachment on their tribal lands. Originally created in watercolour on paper stretching to over a metre in length, each work captures the complex patterning and colour schemes of Australian dollar notes and features an Aboriginal figure distinguished for their fight against colonial invasion and occupation. In surrounding imagery executed in meticulous detail, the artist draws attention to the local contexts in which the dispossession, exploitation and decimation of Aboriginal peoples occurred and upon which the nation’s wealth has been built. The small-scale version of the series reproduced as adhesive stickers – and seen here – enables for the wider circulation and exchange of Presley’s ideas that ultimately question the legitimacy of the nation state.

16

Gordon Bennett

born 1955, Monto, Queensland

died 2014, Brisbane, Queensland

Message in a bottle 1989

oil and synthetic polymer paint on canvas

130 x 260 cm

Collection of Flinders University Museum of Art 2912

© the Estate of Gordon Bennett 2020

There came a time in my life when I became aware of my Aboriginal heritage. This may seem of little consequence, but when the weight of European representations of Aboriginal people as the quintessential primitive ‘Other’ is realised and understood, within discourses of self and other, as a level of abstraction with which we become familiar in our books and our classrooms, but which we rarely feel on our pulses; then you may understand why such an awareness was problematic for my sense of identity. The conceptual gap between my sense of self and other collapsed and I was thrown into turmoil.1

Unaware of his Aboriginal heritage until his teenage years, Gordon Bennett grew up in a Euro-Australian milieu and was schooled in colonial versions of Australian history. He worked as a fitter and turner and Telecom linesman before enrolling in the Queensland College of Art in Brisbane aged 30. Bennett’s experience of endemic racism and growing awareness of his Aboriginal self through the late 1970s and early 1980s would have a profound impact on his subsequent acclaimed practice that included painting, printmaking, performance, video and installation.

Created in the wake of Australia’s Bicentenary, Message in a bottle (1989) is one of a number of ‘Cook’ works made by the artist in direct response to themes fiercely contested and debated in the lead up to and during the anniversary year. Here, the artist deconstructs the iconic portrait of Cook first painted by Nathanial Dance-Holland (1735-1811) in 1776. In the original, Cook is depicted in full naval dress holding his own chart of the Southern Ocean and pointing to the east coast of Australia. Commissioned by Sir Joseph Banks (1743-1820), the portrait makes claim to the ‘discovery’ and ‘possession’ of the Great South Land and affirms Cook’s status as a gallant and noble servant of the expanding British Empire. Positioning Cook in another time and place – within a parched desert landscape strewn with signs and symbols of colonisation including the detached head of Christ – Bennett obscures his subject’s pallid face with blood-red paint to render the explorer deathly and haunting.

1 G Bennett, ‘The Manifest Toe’, in I McLean & G Bennett, The art of Gordon Bennett, Craftsman House, New South Wales, 1996, p9.

17

Gordon Bennett

born 1955, Monto, Queensland

died 2014, Brisbane, Queensland

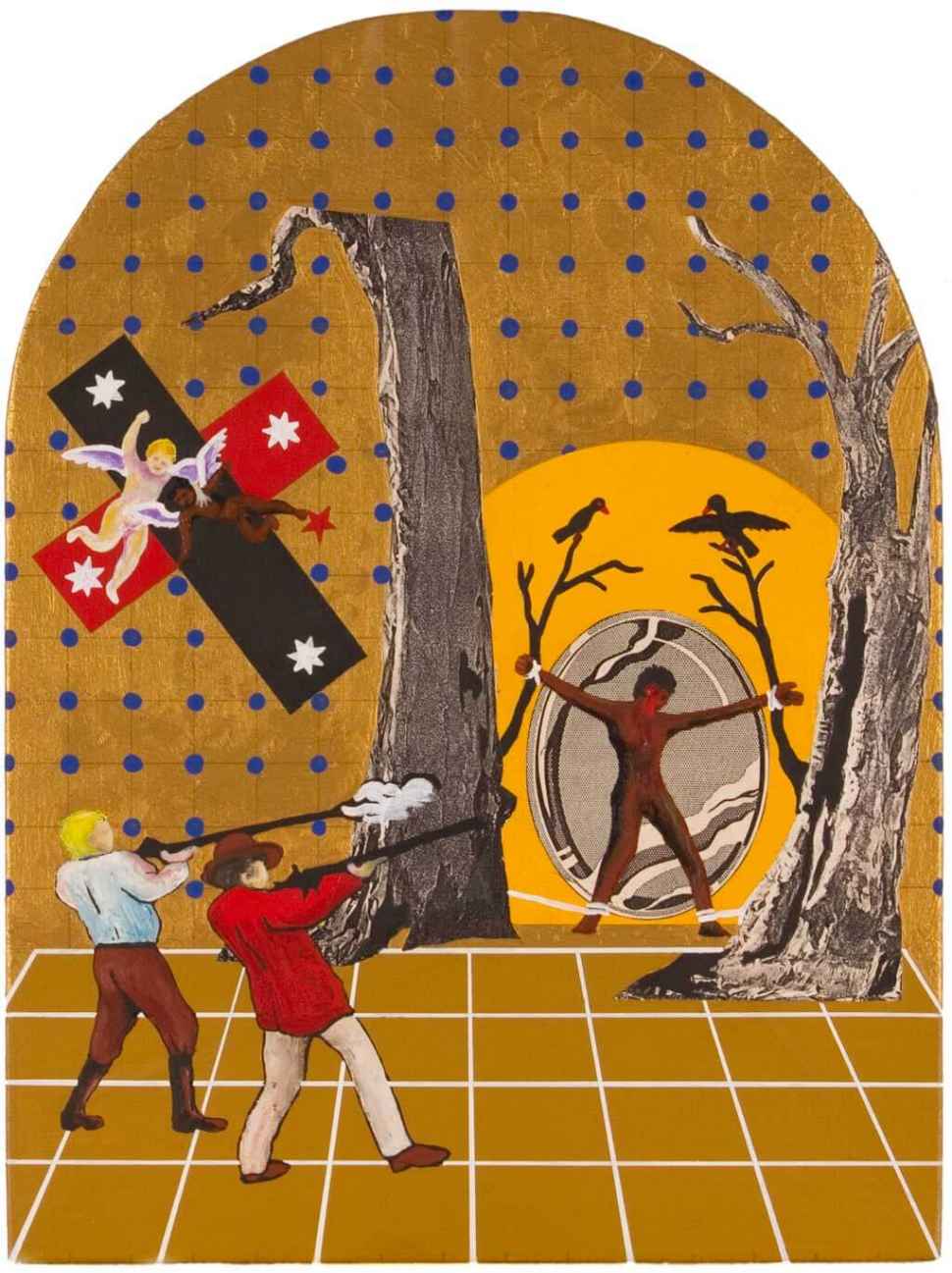

Noonday rest (target practice) 1994

synthetic polymer paint, pencil and paper on board

41 x 31 cm

Collection of Flinders University Museum of Art 3071

© the Estate of Gordon Bennett 2020

If we think of Australia as Narcissus-like, obsessed with its self-image, gazing into the mirror surface of a still pond, then perhaps my work may be understood as one of many disruptions sending ripples across its surface. 1

In disrupting colonial narratives that have forged dominant understandings of Australian history and identity, Bennett’s Noonday rest (target practice) (1994), overturns the myth of peaceful British settlement. The small work painted in the form of a religious icon, incorporates Christian symbolism as seen in the crucifix, the angels and gold paint typically used by the Church to suggest the radiance of heaven. Unlike icons of the Christian church that illustrate the teachings of Christ however, this work unveils failings of Christian doctrine on the colonial frontier. Specifically, Bennett’s image speaks to atrocities that occurred in the Upper Hunter Valley region of New South Wales in the 19th century as recorded by the Wonnarua people, the traditional owners of the area:

In Maitland an Aborigine was captured and accused of a murder which had occurred 65 kilometers away. Seeing the complications of bringing the man to trial, the commanding officer decided on immediate execution. The suspect was tied between two saplings. Various soldiers used him as target practice. The first soldier hit the Aborigine in the back of the neck. The second soldier’s shot blew the Aborigine’s jaw away. The third soldier put his gun against the Aborigine’s face and blew half his head away. No-one ever determined whether the Aborigine was innocent or guilty. 2

1 G Bennett, ‘The Manifest Toe’, in I McLean & G Bennett, The art of Gordon Bennett, Craftsman House, New South Wales, 1996, p62.

2 J Miller, Koori, a will to win: the heroic resistance, survival and triumph of black Australia, Angus & Robertson, Sydney, 1985, p179.

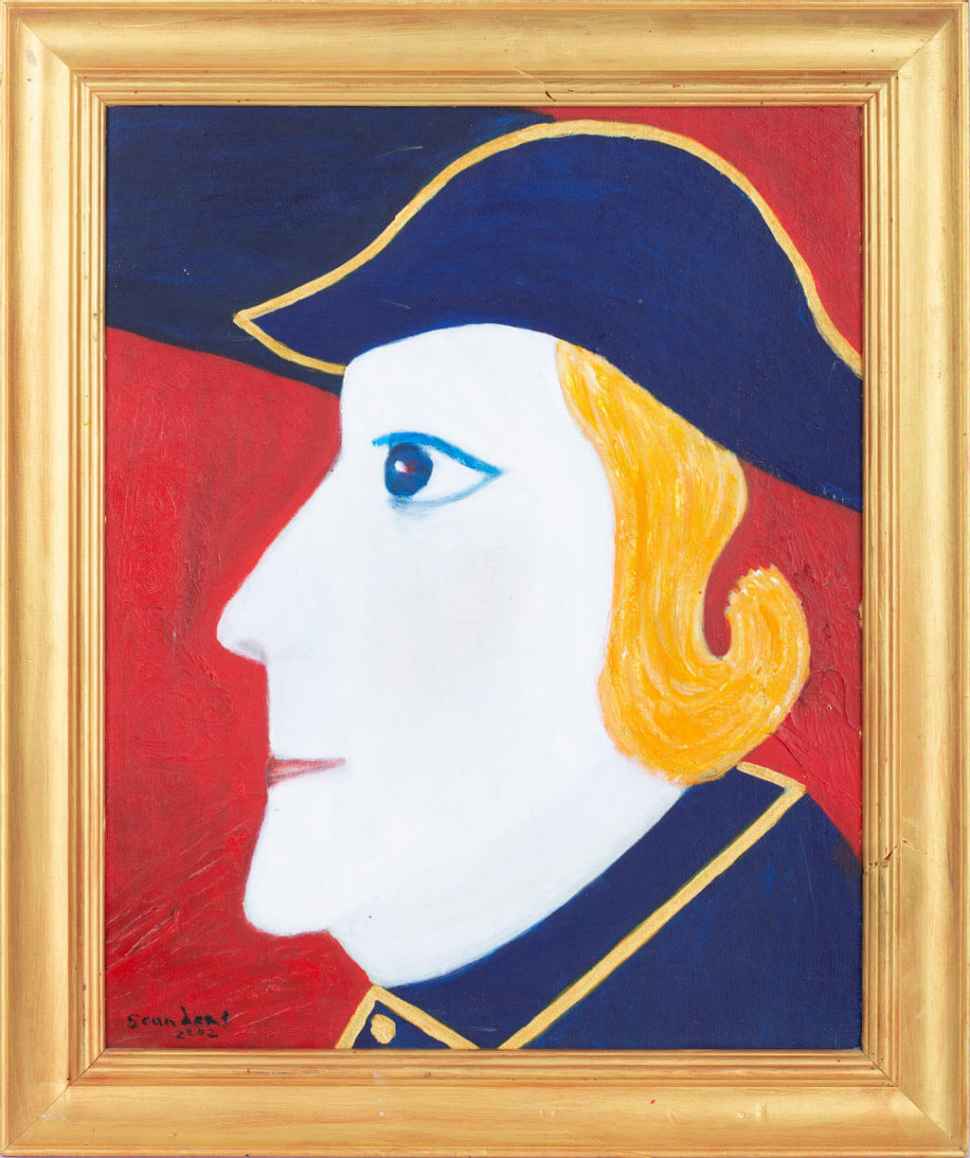

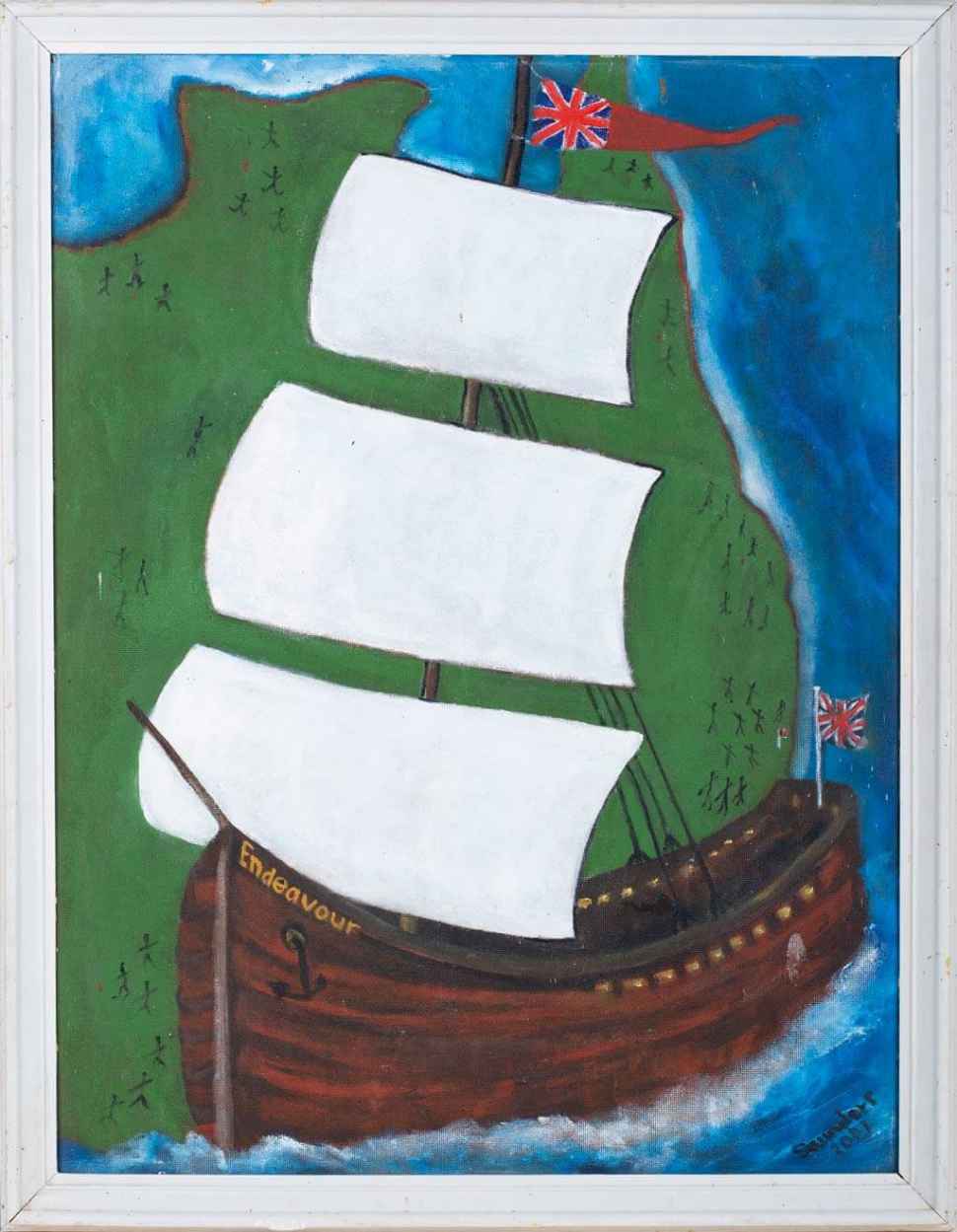

18

Sandra Saunders

born 1947, Millicent, South Australia

Ngarrindjeri people

Portrait of Captain Cook 2002

synthetic polymer paint on canvas board

61 x 51 cm

The Invasion 2001

synthetic polymer paint on canvas board

61 x 59 cm

In the name of the King 2011

synthetic polymer paint on canvas

122 x 40.5 cm

On loan from the artist

© Sandra Saunders 2020

I am an artist and activist. I have always been interested in the history of Aboriginal people and whitefellas and the impact of whitefellas since they came to this country. 1

Sandra Saunders is an artist and activist born in Millicent, South Australia, to a Ngarrindjeri mother and Scottish father. A champion of Aboriginal rights, she was a leader in protests over the construction of the Hindmarsh Island Bridge in the lower River Murray during the 1990s which drew opposition from local residents, environmentalists and Aboriginal leaders. Although the bridge eventually went ahead, a civil case in the Federal Court of Australia vindicated contested claims about the site’s cultural significance for Ngarrindjeri women. The Hindmarsh Island collection, made in direct response to these events saw the creation of Saunders’ first major body of work.

Coming from a place of anguish, Saunders practice is responsive to topical social, political and cultural issues connected to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. As if to capture these stories and events as they unfold, her works are created with a sense of urgency from materials that are readily accessible. These include for example, boards and frames – seen in the works presented here – that are picked up in opportunity shops and repurposed for her paintings.

In her works about Cook, the story of ‘discovery’ and the ‘foundation of Australia’ is recounted with a frankness and simplicity that parallels the Eurocentric version of the nation’s white history. In this version Cook took possession of an empty land ‘in name of the King’, in a seemingly effortless act of planting the British flag into the sand, as illustrated in the work of 2011. The absence of Aboriginal people or signs of their existence in this painting calls to mind the doctrine of terra nullius – the notion of land belonging to no one – that was invoked by the British to justify their acquisition and occupation of Terra Australis Incognita without treaty or payment to Aboriginal and Torres Straits Islander owners.

1 S Saunders, The Hindmarsh Island Collection, catalogue, Adelaide, 2003, p28.

19

Leah King-Smith

born 1957, Gympie, Queensland

Bigambul people

Cross 2007

pigment ink print on cotton rag

104.5 x 107.5 cm, ed. 1/5

Gift of Emeritus Professor JVS Megaw and Dr M Ruth Megaw

Collection of Flinders University Museum of Art 4488

© Leah King-Smith / Copyright Agency 2020

Bigambul descendant Leah King-Smith, is a Brisbane-based artist and academic who investigates the dualities of Indigenous and colonial culture. In her photographic works, she is known for challenging the imperial gaze by merging 19th century ethnographic photographs of Indigenous peoples with imagery of the Australian landscape. Her work Cross (2007) however demonstrates a shift from this subject: the artist utilises less culturally specific imagery to achieve increased ambiguity and explore universal ideas around identity and spirituality.

Cross is one of a series of works that feature cryptic juxtapositions of fragments – in this case the Celtic High Cross, a symbol of early Christianity – together with indistinct monuments and architecture, facial features and varied landscape scenes. These obscured and ambiguous impressions, contained within a lens-like frame, create a sense of depth and movement to evoke the passage of time. King-Smith achieves this through a complicated technical process of layering multiple exposures of pre-existing photographs.

The artist says the following about her photographic technique and methodology:

I am drawn to challenging the camera’s entanglement with colonial imperialism, and the way the lens as canonical device interprets and filters worldviews. In my use of camera, mirror, scanner and photo editor, I choose to layer and sometimes distort multiple lenses and perspectives. By weaving photographic moments and places together, I am constructing a web of connections – of associations that expand the view, as it were, beyond the foreground/middle-ground/background relationships of a one-lens perspective. I could say that my work is ‘photography dreaming’. In museum catalogues and libraries, photographs are more often contextualised within limited temporal terms. 1

1 L King-Smith, artist statement, National Portrait Gallery website, accessed 18 May 2020, <https://www.portrait.gov.au/content/so-fine-leah-king-smith>.

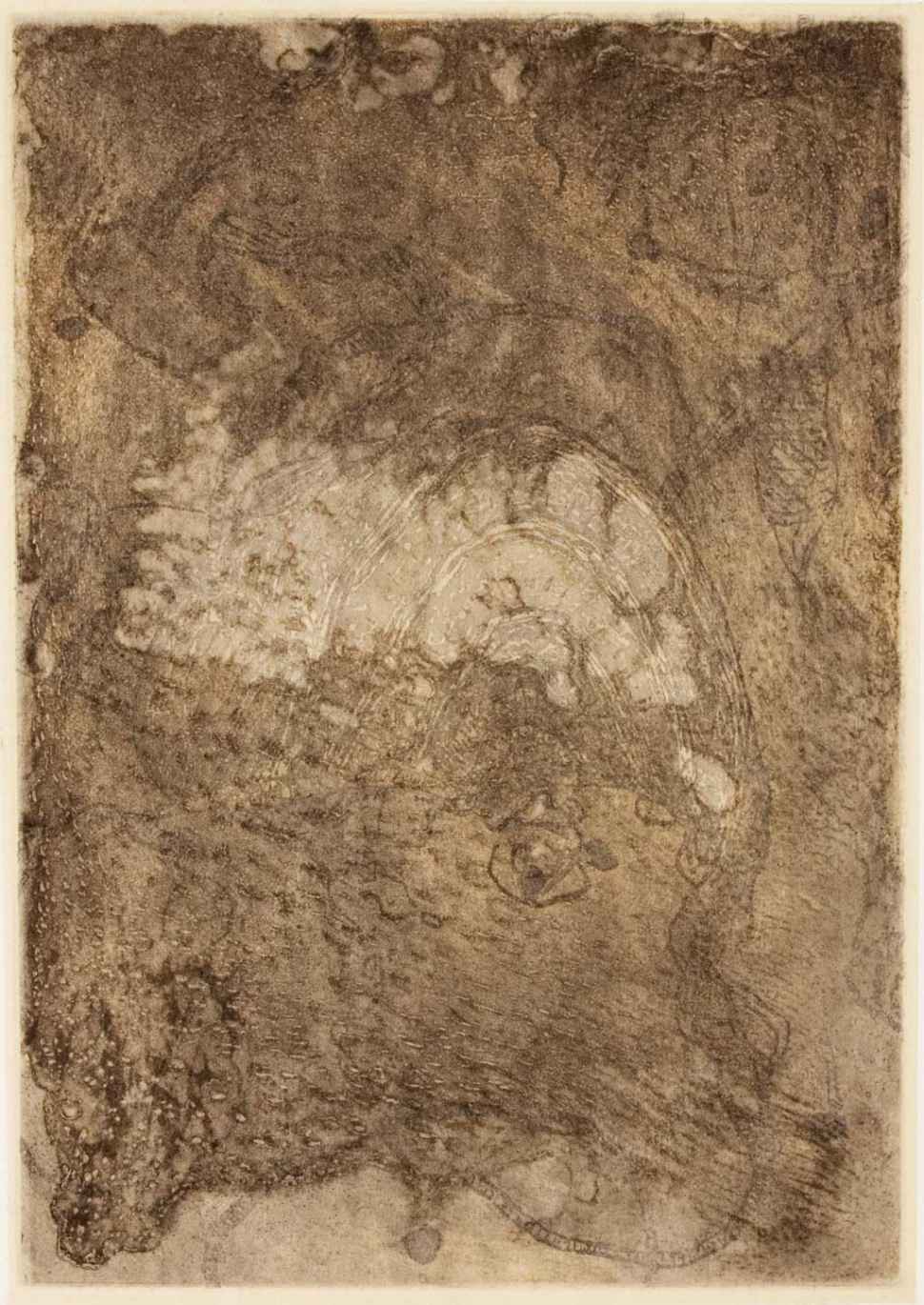

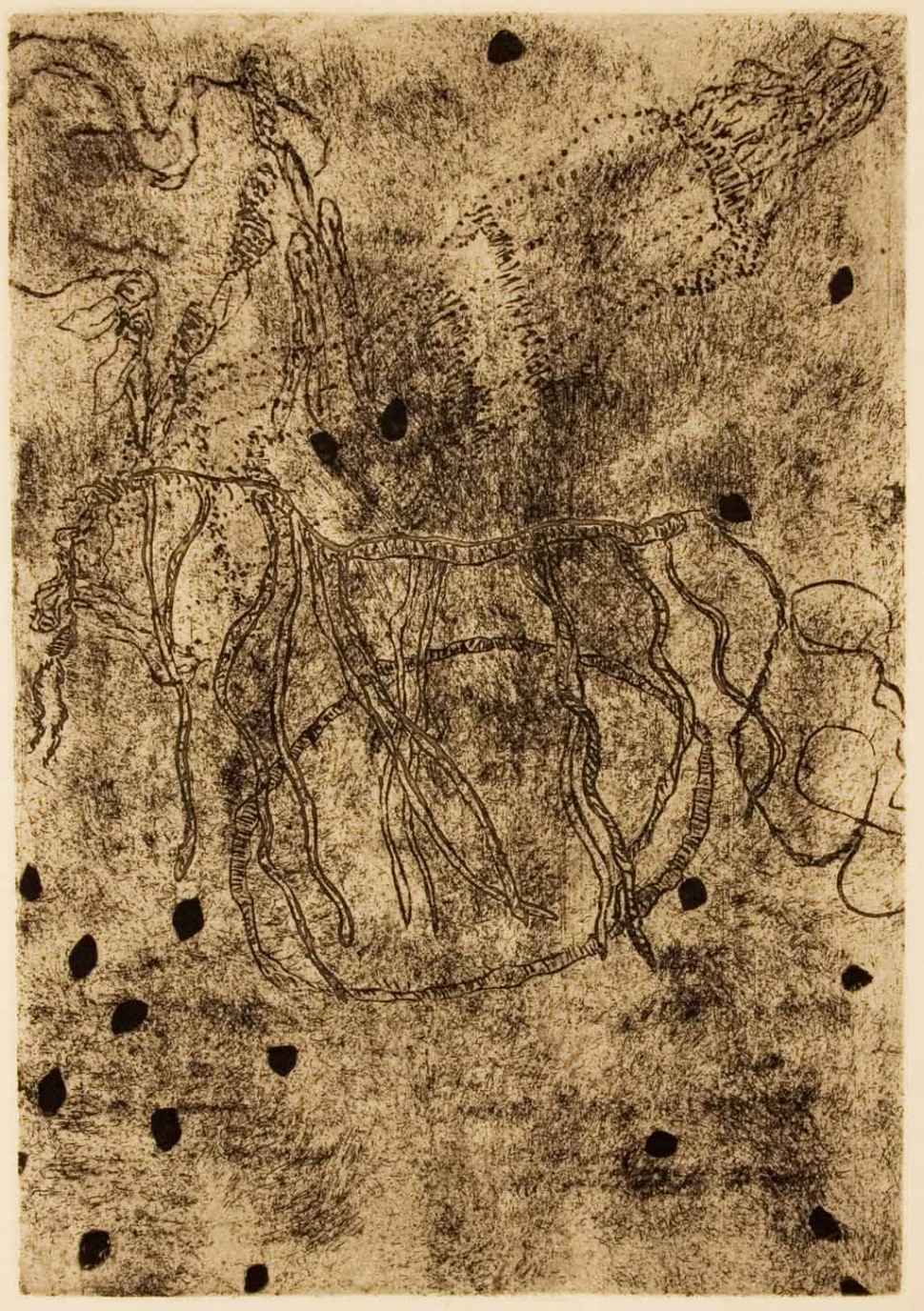

20

Judy Watson

born 1959, Mundubbera, Queensland

Waanyi people

Basil Hall (collaborating artist)

born 1954, Melbourne, Victoria

our hair in your collections 1998

etching, ink and chine collé on paper

30.4 x 21.5 cm, ed. 28/30

our skin in your collections 1997

etching, ink and chine collé on paper

29.8 x 20.1 cm, printer’s proof

Collection of Flinders University Museum of Art 3368, 3367

© Judy Watson 2020

Judy Watson is a prominent Brisbane-based contemporary artist working in the fields of printmaking, drawing, painting, installation and video. Her matrilineal family is from Waanyi Country in North West Queensland and her father’s family have Scottish and English ancestry. Watson says, ‘I fit somewhere in between, I am Indigenous and non-Indigenous. I embody the notion of two cultural frameworks occupying the same cultural space.’ 1

Watson uses her art as a platform of resistance and a way to excavate and bring to light buried histories of Aboriginal experiences on the colonial frontier. While her work is grounded in place and inspired by elements such as earth, water and fire, she also draws on historical and found objects to evoke complex readings and intangible nuances that speak of both loss and the process of reclamation of Country and culture for her family.

Her 1997 etchings, our skin in your collections and our hair in your collections, were made in protest against the active dispossession and institutionalisation of Indigenous people and culture, indexed and stored in museums internationally. During a visit to England in 1995, Watson visited the British Museum, Science Museum and Horniman Museum to view and draw objects and skeletal material collected from her Country in the Gulf of Carpentaria region. She says, ‘When I’ve seen the womens’ pubic fringe objects that have got human hair in them, I think that could have my grandmother’s mother’s hair.’ 2 In the resulting prints, Watson lovingly and respectfully renders her peoples’ armbands, pubic belts and pituri bags, protecting them within a skin of fine paper, so that they oscillate like apparitions, and in doing so she honours and repatriates their memory.

1 J Watson, artist statement, UTS Art website, viewed 13 May 2020, <https://art.uts.edu.au/index.php/judy-watson-a-preponderance-of-aboriginal-blood/>.

2 J Watson & H Perkins, ‘Looking Aboriginal: Judy Watson and Hetti Perkins in conversation’, in T Snell, Sacred ground beating heart: works by Judy Watson 1989-2003, John Curtin Gallery, Bently, Western Australia, 2003, p24.

21

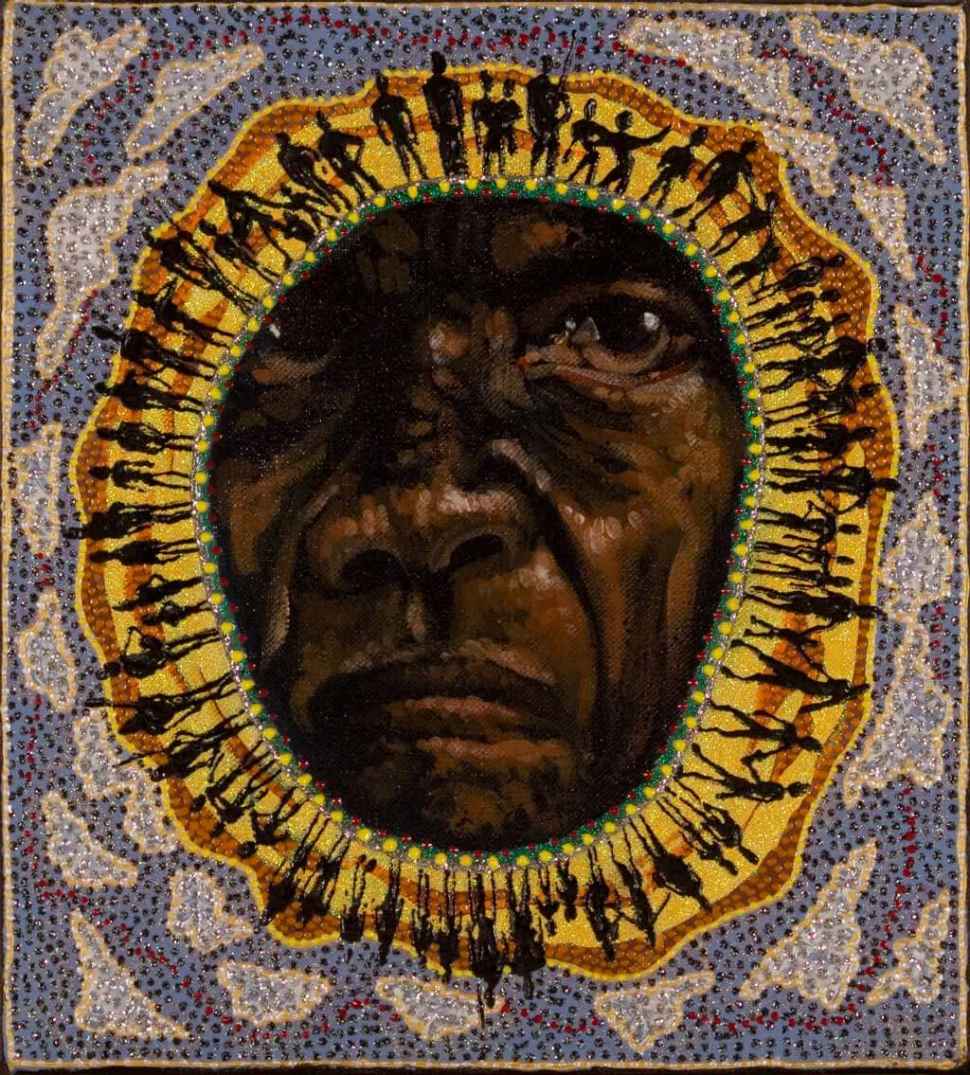

Julie Dowling

born 1969, Perth, Western Australia

Badimaya, Yamatji and Widi peoples

Icon to a stolen child: union 1999

synthetic polymer paint, natural pigments and plastic on canvas

27.7 x 25 cm

Collection of Flinders University Museum of Art 3282

© Julie Dowling / Copyright Agency 2020

Julie Dowling is a contemporary Badimaya artist known for creating emotive paintings of her family. Driven by personal narrative and the politics inherent to survival as a First Nations person, Dowling explores the complexities of her Aboriginal culture and Catholic upbringing. She unmasks blanketed histories relating to the Stolen Generations, forced domestic labour and land rights, calling to attention to the multiplex traumas her communities continue to endure, since colonisation. She says, ‘When you’re First Nation in this country, and lots of places, your life becomes political in lots of ways. My politics...is based on trying to maintain my culture within a dominant...empire.’.1

Icon to a stolen child: union (1999) is a powerful, small-scale painting within a series of over 100 works that Dowling has created since 1996. In the series, the artist remembers and pays homage to her stolen family members and Indigenous children throughout Australia that were systematically and forcibly removed from their communities as part of various State and Federal government policies between 1910-1970. Of the Icon to a stolen child series, Dowling says, ‘They’re an emblematic presence...that represent that we’re still around, that we’re not gone. My family are from about four generations of stolen kids, so they sort of represent what we are, and I have a lot of family members in the pictures.’.2

The seductively sparkling work Union is an icon to Dowling’s great-great-aunt and venerates and reclaims her life as a stolen child. Glittering Western Desert and Christian iconography encircles and radiates out from the portrait of the artist’s relative whose gaze uncompromisingly confronts the viewer. In this work, the great-great-aunt is depicted at the centre of a meeting place, reunited with her dislocated family and community, who surround her – like sentinels – as a succession of silhouetted figures against her sandy Country.

1 J Dowling, YouTube website, accessed Thursday 21 May, <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bxW8bF2pLPg>.

2 ibid.

22

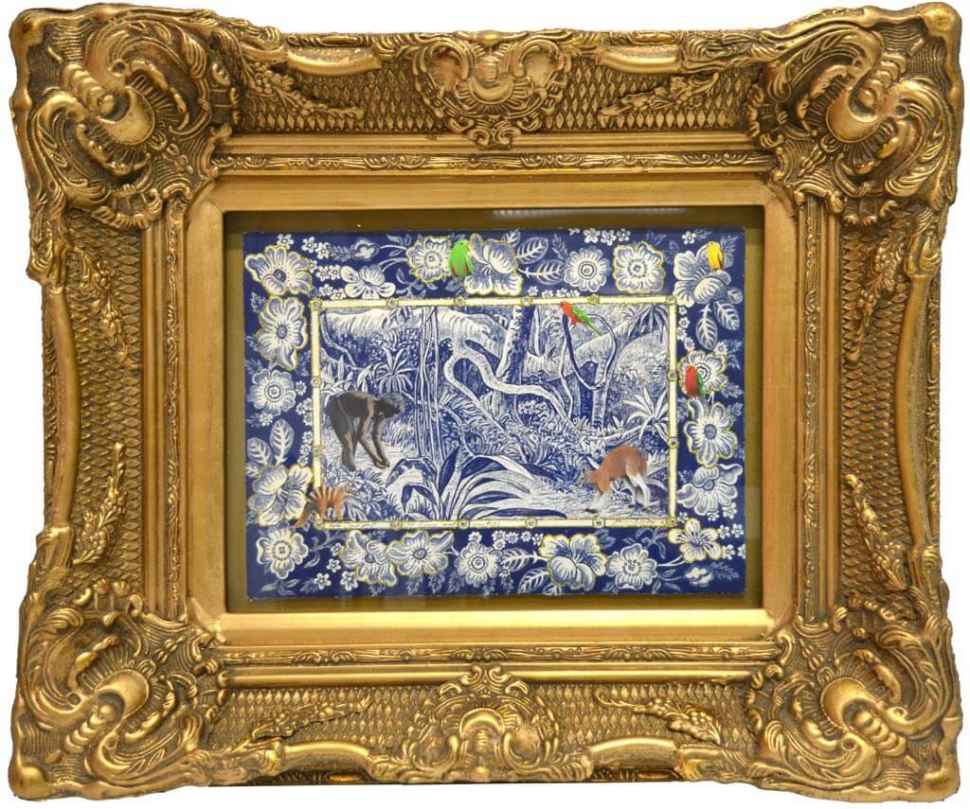

Danie Mellor

born 1971, Mackay, Queensland

Mamu, Ngagen and Jirrbal peoples

Bala Jindigal (spirit home in ground) 2014

pastel, pencil and wash with crystal and glitter on paper

27 x 37 cm

Commissioned by Emeritus Professor JVS Megaw in memory of Dr M Ruth Megaw

Collection of Flinders University Museum of Art 4959

© Danie Mellor 2020

Danie Mellor is a multidisciplinary artist who investigates the collision and transformation of cultures since, what he refers to as, ‘post-settlement’ 1 Australia. He draws inspiration from his European and Mamu, Ngagen and Jirrbal heritage and in particular, his Country in the Atherton Tablelands of Far North Queensland. He says:

There’s always a focus for me, which is at the intersection between Indigenous and Western. At the heart of that is the narrative around Country and nature: the experience of a particular ecology and environment, which gives rise to the stories that are so critically important in cultural practice for the passing on of knowledge... 2

Mellor is known for creating richly imagined and textured hybrid-worlds by combining 18th and 19th century imagery and symbols with the lush scenery of northern Queensland rainforests, challenging perceptions of the ‘Other’. He states:

...as an artist I am a story teller whose work engages with dual cultural perspectives and the intersections of human experience. Opening up a critical dialogue about people, Country, landscape and the perception around that is one of the key areas of my practice. 3

The blue and white palette and borrowed floral border in, Bala Jindigal (spirit home in the ground) (2014), is a direct reference to 18th and 19th century Spode china, which for Mellor alludes to both exoticism and colonial imperialism. The elaborate gilt frame as well as the glitter and high-end crystal bling, seduce the viewer, drawing attention to the central image – a portal – into Mellor’s Country in the tropics, where Australian animals watch over an ancestor who gathers from the earth that which is not visible: he is connecting with the ‘spirit home’ of the land.

1 M Palmer, ‘Introduction’, in M Palmer, ed., Danie Mellor: exotic lies sacred ties, The University of Queensland Art Museum, Brisbane, 2014, p17.

2 H Perkins & D Mellor, ‘Parallel worlds: Hetti Perkins and Danie Mellor in conversation’, in M Palmer, ed., Danie Mellor: exotic lies sacred ties, The University of Queensland Art Museum, Brisbane, 2014, p57.

3 Palmer, op. cit., p21.

23

Julie Gough

born 1965, Melbourne, Victoria

Trawlwoolway people

Promissory note - opposite Swan Island 2005

timber, tea tree, possum fur, string and pokerwork

229 x 240 x 130 cm

Gift of Emeritus Professor JVS Megaw and Dr M Ruth Megaw

Collection of Flinders University Museum of Art 4388

© Julie Gough 2020

Hobart-based, multidisciplinary artist Julie Gough investigates, unravels and exposes subsumed and conflicting Australian histories. In doing so, she gives voice to the lives and experiences of Tasmania’s Aboriginal peoples since European contact and the frontier wars of the 1820s, to the present day. Gough’s work is driven by personal narrative: her journey of reconnecting with her maternal Trawlwoolway and paternal Scottish and Irish ancestry through the process of remembering, reclaiming and re-presenting the histories associated with Tebrikunna, her Country in far north-eastern coastal Tasmania. Gough states she is motivated by the necessity to, ‘translate into inviting and approachable visual art forms the written and subsumed histories of cultural invasion, collision and trauma that has plagued Tasmania, Australia and Indigenous peoples everywhere.’.1

Promissory note – opposite Swan Island (2005), represents what the artist refers to as an ‘incomplete transaction, our unfinished business’:2 a promise issued by George Augustus Robinson (1791-1866) on behalf of the British Government to Gough’s family that was not upheld. On 6 August 1831, Robinson’s journal states:

This morning I developed my plans to the chief Mannalargenna and explained to him the benevolent views of the government towards himself and people... I informed him...that I was commissioned by the Governor to inform them that, if the natives would desist from their wonted outrages upon the whites, they would be allowed to remain in their respective districts and would have flour, tea and sugar, clothes & c given them; that a good white man would dwell with them who would take care of them and would not allow any bad white man to shoot them, and he would go about the bush like myself and they then could hunt. 3

Four years later, First Nations leader Mannarlargenna (c1775-1835) was relocated to Flinders Island, in the Bass Strait, where many Tasmanian Aboriginal peoples were exiled to confinement, often resulting in disease and death. Mannarlargenna, who cut his hair in mourning the loss of his Country, died on Flinders Island one month later from pneumonia.

In Gough’s installation, set against the silhouetted view of Swan Island, bound spears carved from tea tree and seared with Robinson’s promised words symbolise surrender: the laying down of weapons by Mannarlargenna and his people so they could freely occupy their Country. The sun-like assemblage represents light and for the artist is a metaphor for loss, she says, ‘...countless unlit firesticks... Awaiting re-ignition, these bare bones of traditional means of warmth, light, meals shared and stories told have been essentially extinguished over the past 200 years through the actions of European invasion.’.4

1 J Gough, artist statement, 2005, Flinders University Museum of Art archive file 4388.

2 ibid.

3 NJB Plomley ed., Friendly mission: the Tasmanian journals and papers of George Augustus Robinson, 1829-1834, Tasmanian Historical Research Society, Hobart, Tasmania, 1966.

4 Gough, op. cit.

24

Vincent Namatjira

born 1983, Alice Springs, Northern Territory

Western Aranda people

Close Contact 2018

synthetic polymer paint on plywood

188 x 62 x 3.5 cm

Gift of the James & Diana Ramsay Foundation for the Ramsay Art Prize 2019

Collection of Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide 20193S2

© Vincent Namatjira/ Copyright Agency 2020

Born in Alice Springs, Vincent Namatjira grew up Perth. He returned to Hermannsburg to reconnect with his Western Aranda heritage on completing high school. It was not until his journey back to central Australia that he learned about his connection to the celebrated watercolourist Albert Namatjira (1902-1959) and extended family of acclaimed artists. Vincent Namatjira now lives and works at Indulkana on the Anangu Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara Lands in the north-west of South Australia where he has been painting since 2011.

Namatjira’s figurative painting is recognized for its vivid palette, unlikely composition and deep sense of humour. Offering a droll take on the politics of history, power and leadership from a contemporary Aboriginal perspective, his work features figures of personal and political significance, often in juxtaposition with each other. In the double-sided portrait of Cook presented here, the artist departs from his wall-based paintings on canvas using plywood to fashion a two-dimensional form. Working from life and reference images, including E. Philips Fox’s (1865-1915) painting Landing of Captain Cook at Botany Bay, 1770, the resulting double-sided figure effortlessly embodies the complex, contested and seemingly irreconcilable narratives of our nation. Namatjira says:

The title Close Contact refers to the idea of ‘first contact’ between Indigenous Australians and Captain James Cook. I wanted to play around with the idea of the heroic portrait of Cook that we’re all used to seeing and with the double-sided painting I’m trying to say ‘there’s two sides to every story’ with a bit of a cheeky sense of humour. 1

1 V Namatjira, artist statement, Ramsay Art Prize 2019 postcard, Art Gallery of South Australia, 2019.

Flinders University Museum of Art

Flinders University I Sturt Road I Bedford Park SA 5042

Located ground floor Social Sciences North building, Humanities Road adjacent carpark 5

Telephone | +61 (08) 8201 2695

Email | museum@flinders.edu.au

Monday to Friday | 10am - 5pm or by appointment

Thursdays | Until 7pm

Closed weekends and public holidays

FREE ENTRY

Flinders University Museum of Art is wheelchair accessible, please contact us for further information.