Paola Balla

born 1974, Footscray, Victoria

Wemba Wemba and Gunditjmara people

Born Into Sovereignty, Live In Sovereignty 2014

1950’s house dress with emu feathers and assorted native bird feathers

On loan from the artist

© the artist

Wemba Wemba and Gunditjmara woman Paola Balla is an artist, curator, writer and academic who lives and works in Footscray, Naarm/Victoria. She is currently Director of Teaching and Learning at the Moondani Balluk Indigenous Academic Unit, Victoria University. Her research-based practice is embedded in a ‘sovereign act, in both process and outcome for expressing blak matriarchy and First Nations ways of being, knowing and doing.’1 Balla’s practice pushes back against white patriarchal and colonial narratives to demonstrate the ongoing social injustices and colonial trauma still experienced by Aboriginal women and children.

Born Into Sovereignty, Live In Sovereignty presents a floral 1950s housedress that has been embellished with a collar of bird feathers and skirt of fine emu feathers. Balla comments,

This is a memory work about my grandmother Rosie who had to combat and survive working as a domestic for white women in Echuca and violence, poverty and racism, working on cattle station the Echuca laundry , and segregation when she was made to give birth on th verandah of the Echuca Hospital in the 1950s, as many other Aborignal women did, through to creating places of survival for her children in the bush on our Wemba-Wemba Country and Yorta Yorta Country at Echuca. Nan Rosie went on to become an artist and adoring grandmother.

1 P Balla, Victoria University, accessed 22 September 2021 <https://www.vu.edu.au/research/paola-balla>

Ellen Trevorrow

born 1955, Raukkan/Point McLeay, South Australia

Ngarrindjeri people

Sister basket, 1998

woven sedge grass

Collection of Flinders University Museum of Art 3246

© the artist

Ngarrindjeri elder Ellen Treverrow is a highly skilled and renowned cultural weaver based in Meningie, South Australia. As a child, Treverrow watched her grandmother weave but only learnt herself in the early 1980s while attending a workshop run by the late elder Aunty Dorothy Kartinyeri. Kartinyeri not only taught participants how to weave but also how to source and prepare the rushes which grow in sandy soil along the Coorong and River Murray.1 Since then, Treverrow has continued this cultural tradition and shares her knowledge through her weaving and storytelling practice as a means of cultural restoration and continuation.

Treverrow’s Sister Basket, or in Ngarrindjeri a Nakal, is made from two identical ‘sister’ faces. Treverrow, with the assistance of her husband Tom, relearnt the method to create the sister basket by studying a historical example created by Ethel Whympie, Tom’s great grandmother, held in Camp Coorong’s collection.2 To create the baskets, clumps of sedge grass are bundled together, then coiled on itself and bound with a single reed, the two finished faces finally woven together. In Ngarrindjeri culture both men and women weave mats and utensils such as egg scoops, as well as the baskets they needed to carry babies, spears, and food. Sister baskets were used to collect herbs and carry small objects.

1 L Fisher, Ellen Trevorrow, Design & Art Australia Online, 2011, accessed 22 September 2021 <https://www.daao.org.au/bio/ellen-trevorrow/biography/>

2 Ibid

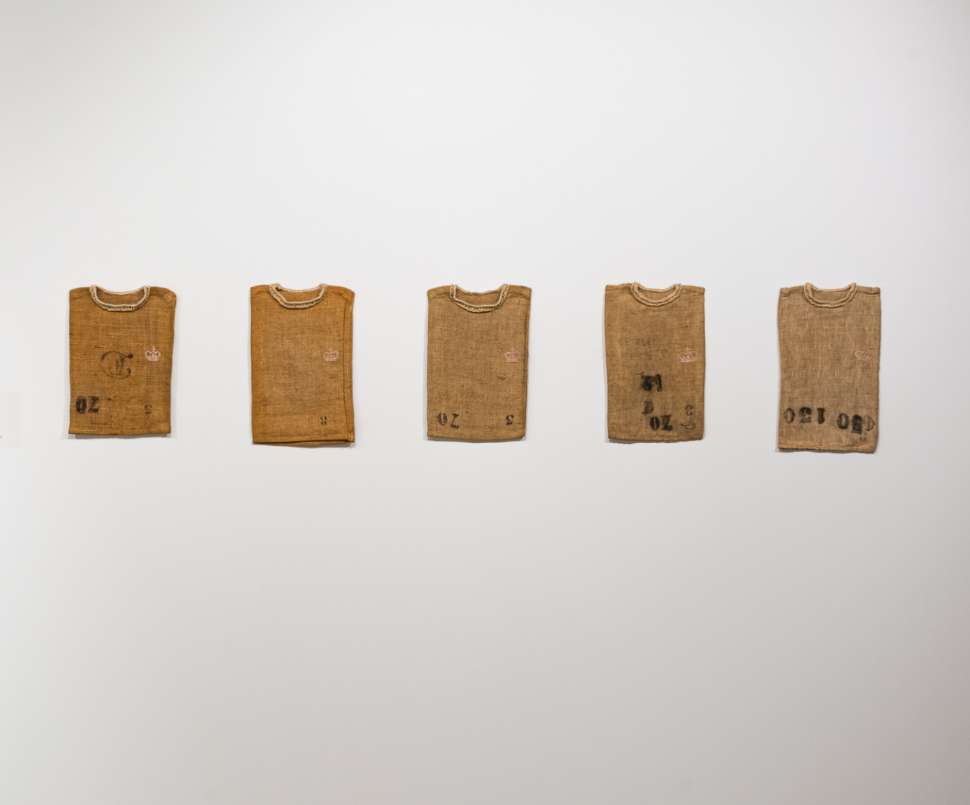

D Harding

born 1982, Moranbah, Queensland

Bidjara, Ghungalu and Garingbal people

bright eyed little dormitory girls 2013

hessian, mohair wool

Collection of Museum of Contemporary Art 2013.61A-E

Purchased with funds provided by the MCA Foundation, 2013

© the artist

Brisbane-based artist D Harding is a descendant of the Bidjara, Ghungalu and Garingbal people of Central and Western Queensland. His multi-disciplinary practice draws on his matrilineal heritage to highlight the oppression of Australia’s First Nations people and the falsehoods perpetuated by the colonial archive. Harding often collaborates with his family to articulate their painful oral histories.

Harding’s mother, grandmother, and great-grandmother were all forced into domestic servitude within white Australian households and estates. This work is a poetic response to his grandmother’s experience of domestic slavery following her forcible relocation to the Woorabinda Mission, Queensland. While undertaking unpaid work she had to avoid the unwanted advances of an employer and fought him off with a mop and bucket. As punishment, she was forced to work in a coarse hessian dress.1 Harding’s five, neatly folded hessian sacks with absent armholes reflect the confinement and control of Aboriginal women, while the delicately sewn mohair collars refer to uniforms worn by Aboriginal domestics.2 Each object is embroidered with a soft pink crown and stencilled with an ‘inmate’ number reflective of the state and government bodies which implemented racially oppressive policies such as indentured labour and the removal of Indigenous women and children from their homelands and communities.

1 D Harding, Bright Eyed Little Dormitory Girls, Queensland College of the Art, Griffith University, 2013, pg 18

2 Ibid, pg 24

Unbound Collective

Active 2014 –

Kaurna Yarta, Adelaide, South Australia

Ali Gumillya Baker

born 1975, Rose Park, South Australia

Mirning people

Faye Rosas Blanch

born 1959, Atherton Tablelands, Queensland

Mbararam and Yidinyji people

Natalie Harkin

born 1970, Adelaide, South Australia

Narunnga people

Simone Ululka Tur

born 1971, Adelaide, South Australia

Yankunytjatjara people

Jessica Wallace (editor)

Days of Our Lives 2021

for exhibition APRON-SORROW / SOVEREIGN-TEA curated by Natalie Harkin, presented by Vitalstatistix

video, duration 16:16 mins

On loan from the artists

© the artists

Formed in 2014 the Unbound Collective comprises First Nation women, artists, poets, and academics – Ali Gumillya Baker, Faye Rosas Blanch, Natalie Harkin and Simone Ulalka Tur. Through their research based, critical-creative practice, which features performance, video and installation, they challenge the colonial narrative and archive by reinstating Aboriginal and Torres Islander voices and perspectives. Their performance and poetics draw on memory and storytelling to investigate colonial notions that have historically bound Indigenous people and communities. Through their work they explore how they can be unbound from this history.

Days of Our Lives (2021) represents the Unbound Collective’s individual ‘memory stories’ which reimagine the legacies and histories of domestic servitude from each of their families. Natalie Harkin writes, ”These stories are epic and drawn out to be the hidden backdrop to our collective lives. This is a small window to the embodied archive, sharing what our women endured living under, particularly those state regimes of surveillance and control under the Aborigines Protection Act. Here, we honour all Aboriginal women who laboured so hard. This work is overwhelmingly about their strength, resilience and love.”1

1 N Harkin, personal correspondence with M Reece, 22 September 2021

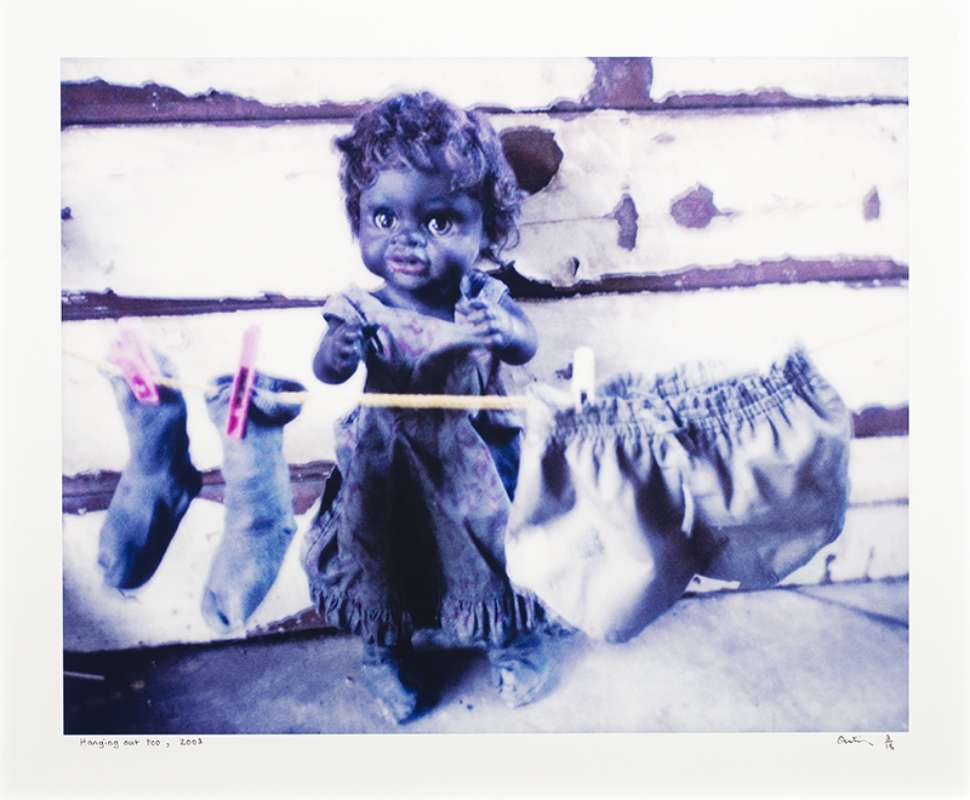

Destiny Deacon

born 1957, Maryborough, Queensland

Erub, Meriam Mer and KuKu people

Hanging out too 2003

lightjet print from a polaroid original

Gift of Julian and Stephanie Grose through the Art Gallery of South Australia Contemporary Collectors 201. Donated through the Australian Government’s Cultural Gifts Program

Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide 20172Ph1

Destiny Deacon is an artist, academic and activist based in Naarm/Melbourne, Victoria, who employs satire and humour to redress casual everyday racism and interrogate the oppression of First Nations people. A descendant of the Meriam Mir and Erub people of the Torres Strait and Ku Ku people of Cape York in far north Queensland, Deacon’s photography, video and installation work utilises her ‘Koori Kitsch’1 collection to highlight white Australia’s engrained assumptions about Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

Hanging out too presents a polaroid snapshot of a black doll hanging out the washing outside a weatherboard house. The title could be read casually as a woman doing everyday things but upon closer inspection, we see that the work comments on the objectification and racialised stereotypes of people of colour. Deacon has utilised ‘the dolls’ across her thirty-year practice, commenting:

“The dolls, the black dolls, I felt sorry for them, and the kitsch stuff. And they sort of represent us as people, because white Australia didn’t come to terms with us as people … [the dolls are] objects, and that’s the way that white Australia saw us: the flora, the fauna, and the objects. And I just thought, well, they’ve just as much to say.” 2

Within Hanging out too, Deacon recalls the unjust treatment and indentured labour of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women and children. Her photographs and practice, while humorous and satirical, reveal painful histories.

1 V Fraser, Destiny’s Dollys, Photofile, Issue 40, 1993, pg 209

2 S Convery, Destiny Deacon on humour in art, racism, ‘Koori kitsch’ and why dolls are better people, The Guardian, 2020, accessed 16 September 2021 <https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2020/nov/24/destiny-deacon-on-humour-in-art-racism-koori-kitsch-and-why-dolls-are-better-than-people>

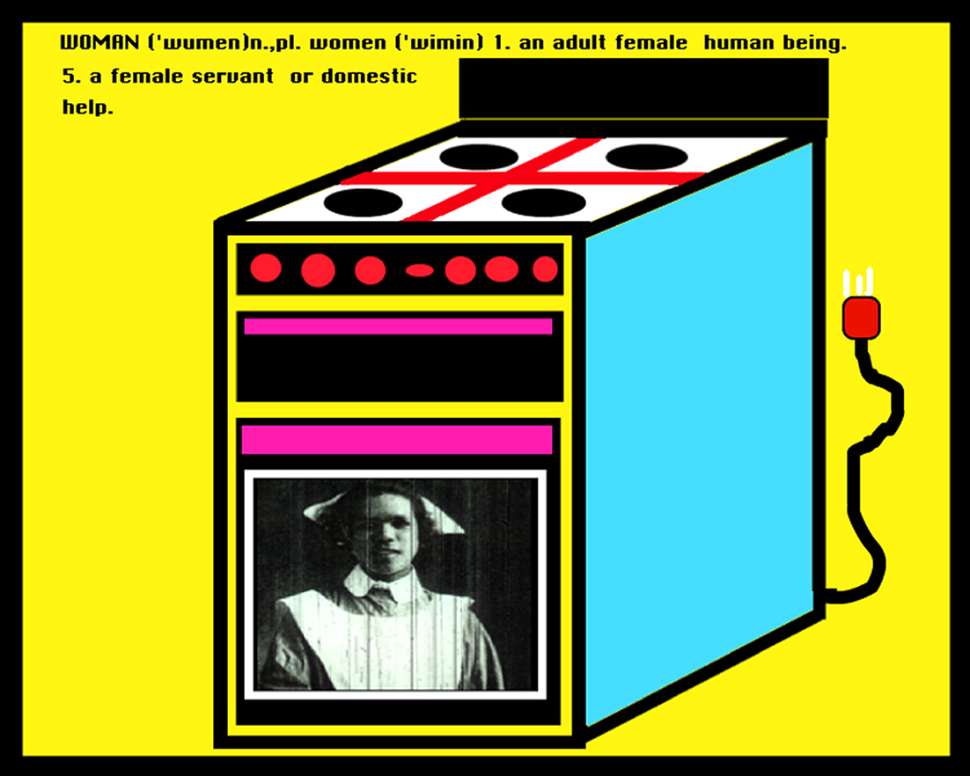

r e a

born 1962, Coonabarabran, New South Wales

Gamilaraay, Wailwan and Biripi people

Look Who’s Calling The Kettle Black 1992

10 dye sublimation prints

On loan from the artist

© the artist

r e a is a Gamilaraay, Wailwan and Biripi artist, curator, academic and activist based between Brisbane, Queensland and the Blue Mountains, New South Wales. Her research-based visual arts practice, which spans three decades, employs photography and new media processes to investigate the critical discourse and intersectionality of Aboriginality within the disciplines of creative arts, Australian history, and colonisation as well as gender and identity politics.

Look Who’s Calling The Kettle Black was created while r e a was completing a Bachelor of Fine Arts (Visual Arts) at the College of Fine Arts, University of New South Wales, and was the first body of work exhibited by the artist. The series juxtaposes archival photographs of Aboriginal women working as domestic servants with textbook definitions and derogatory, racially profiled terms used to describe them. The photographs are superimposed onto crude computer graphic imagery of pop-coloured household items such as kettles, frypans and irons. Within this series r e a highlights how colonial constructs of domestic female identity, have been imposed upon First Nations women.

r e a

born 1962, Coonabarabran, New South Wales

Gamilaraay, Wailwan and Biripi people

PolesApart 2009

HD video, duration 6:55 mins

On loan from the artist

© the artist

r e a is a Gamilaraay, Wailwan and Biripi artist, curator, academic and activist based between Brisbane, Queensland and the Blue Mountains, New South Wales. Her research-based visual arts practice, which spans three decades, employs photography and new media processes to investigate the critical discourse and intersectionality of Aboriginality within the disciplines of creative arts, Australian history, and colonisation as well as gender and identity politics.

Drawing inspiration from her earlier series Look Who’s Calling The Kettle Black, PolesApart continues r e a’s investigation into Australia’s colonial history and the scars this brutal legacy has left upon the body and minds of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. PolesApart is a moving image artwork which presents r e a as the protagonist, dressed in a Victorian-era black mourning gown. In this silent video we glimpse an Aboriginal woman running through a charred landscape. She intermittently pauses to catch her breath, stumbles but picks herself up, and hides behind singed foliage. While we never see her pursuers, their impending presence is anxiously felt. Based on the experiences of r e a’s grandmother and great aunt, and circumstances relating to the Stolen Generation of Aboriginal children, PolesApart illustrates a personal, family story and a desire to escape the clutches of unjust policies which enforced assimilation and domestic enslavement of Aboriginal women and children.

Ali Gumillya Baker

born 1975, Rose Park, South Australia

Mirning people

SovereignGODDESSnotdomestic #2 2017

featuring Natasha Wanganeen

digital photograph on lightbox

On loan from the artist

© the artist

Ali Gumillya Baker is a Mirning woman from the Nullarbor on the West Coast of South Australia and a multidisciplinary artist and educator. In 2018 she was awarded a Doctorate of Philosophy in Cultural Studies and Creative Arts from the same institution. Currently Senior Lecturer in the College of Humanities, Arts and Social Sciences at Flinders University, Baker’s research interests are colonial archives, memory and the intergenerational transmission of knowledge. As well as working as an independent artist, Baker is a member of the Unbound Collective which was formed in 2014 with colleagues Faye Rosas Blanch, Natalie Harkin and Simone Ulalka Tur.

The series SovereignGODDESSnotdomestic are portraits of First Nations women in her community on Kaurna Yarta, Adelaide, South Australia. Each sitter holds a decorative gold guilt frame, and their strong and defiant gaze holds the eyes of the viewer, countering colonial scrutiny. This work honours the women in Baker’s family, in particular her Nana’s older sister Ruby Boxer who worked as a domestic for forty years without a wage. This is recorded on her protector files.

Artist Unknown

Jemima, wife of Jacky with William Tennant Mortlock c1860

daguerreotype, colour dyes in pressed leather case

Collection of National Trust of South Australia AH0784

Taken in the mid-19th century this daguerreotype captures Aboriginal woman Jemima with her ward, the son of South Australian pastoralist William Ranson Mortlock (1821-1884), after whom the Mortlock Wing at the State Library of South Australia is named. Jemima and her husband Jackey Gunlarnman worked for Mortlock at the Yalluna Station on Eyres Peninsula.1 Jemima is captured here in full colonial dress with lace collar, her hair carefully curled, and William Tennant Mortlock in her arms. She appears proper and professional for the portrait while the toddler is blurred, no doubt due to the photograph's long exposure time.

A sense of equity is portrayed in this image as well as the accompanying story that claims Mortlock ‘saved’ Jackey and convinced him to work at Yalluna, giving he and Jemima a ‘three roomed house’.2 Contact histories of the region shatter this illusion with evidence proving that Mortlock upheld violent treatment, including whipping and lashing, of Aboriginal workers with some dying from their injuries.3 Through this lens the portrait of Jemima captures a white patriarchal class system, where she is merely Mortlock’s domestic servant and his son’s nanny.

1 J Lydon, Jackey and Jemima Gunlarnman, Calling the Shots: Aboriginal Photographies, 2014, Aboriginal Studies Press, pp159-160

2 Ibid, pp159-160

3 Ibid, pp159-160

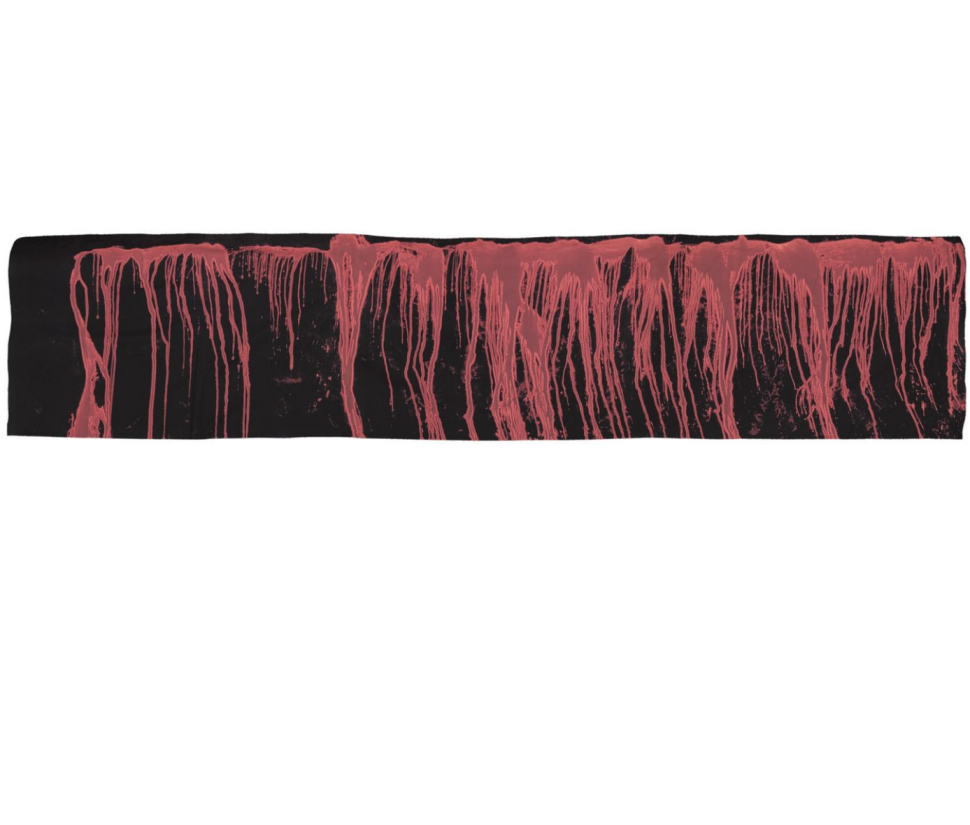

Clinton Naina

born 1971, Carlton, Victoria

Meriam Mir, Erub and KuKu people

Red reign 2001

bleach on Indian cotton

South Australian Government Grant 2001

Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide 20017P16

Clinton Naina is a painter, dancer, performer, storyteller, and descendent of the Meriam Mir and Erub people of the Torres Strait and the Ku Ku people of Cape York in far north Queensland. Living and working in Naarm/Melbourne, Victoria, their practice brings together performance art and abstract expressionism to create politically charged imagery that exposes the truth and cruelty of Australia’s colonial settlement and its ongoing legacy.

Red reign from Naina’s exhibition Whitens, Removes Stains, Kills Germs presented at Sherman Galleries, Sydney continues ideas explored in Naina’s seminal body of work White King, Blak Queen (1999). In Red Reign Naina uses bleach to illustrate the traumas of colonisation from a queer and black feminine viewpoint. He embodies the persona of the Blak Queen in her quest for equality by protesting against white male patriarchy. The romantic and violent gestural stains of Red reign recall the words of John Harding, the artist’s brother:

The Blak Queen is omnipotent, knows no boundaries and recognises no colonising fences… She can turn everyday household items into weapons against colonisation and the fading of memory. Her splashes of bleach become evocative images of lingering memories, prodding us to remember the truth. 1

1 J Harding, Whites, removes stains, kills germs!, Sherman Galleries, Sydney, 2001, pg 1.

Leah King-Smith

born 1957, Gympie, Queensland

Bigambul people

Untitled #11 from the series Patterns of connection 1991

direct positive colour photograph

The Vizard Foundation Art Collection of the 1990s, acquired 1994

On loan from the Ian Potter Museum of Art, the University of Melbourne

Bigambul descendant Leah King-Smith is a Brisbane-based artist and academic who investigates the dualities of Indigenous and colonial culture. In her photographic works she challenges the imperial gaze by merging 19th century ethnographic photographs of Indigenous peoples with imagery of the Australian landscape.

In the series Patterns of connection, Leah King-Smith seeks to decolonize 19th century ethnographic portraits of First Nations people held in the Pictures Collection at the State Library of Victoria. These portraits were taken on Christian Missions and Aboriginal reserves where forced assimilation policies removed Aboriginal people from Country and obliged them to uphold the customs of Anglo-European culture. These portraits were commissioned to capture a ‘dying race’ and were used as source material to classify and categorise Aboriginal people. In protest, King-Smith’s hand-coloured compositions in Patterns of connection remain ‘untitled’ as a means to counter colonisation and racialised processes of classification. In Untitled #6 she superimposes a photograph of four Aboriginal women seated in colonial dress with the Australian landscape as a means of ‘returning them to their land’.1

1 J Phillips, Elegy, meditation and retribution, Patterns of Connection, 1991, pp 17-19

Tracey Moffatt

born 1960, Brisbane, Queensland

Up in the Sky #12 1997

off-set print, ed 14/60

Monash University Collection 1998.16

Sydney-based artist Tracey Moffatt’s work spans four decades. She uses photography and film to create dramatic, and highly staged, photo-narratives. Moffatt combines her own experiences and imagination with the history of art, film, photography and popular culture. Moffatt’s visual practice characteristically presents ‘incidents and vignettes depicting disturbing, tender, funny and cinematic sequences’1 which explore concerns around the representation of race, gender and identity.

Up in the sky was created soon after Bringing Them Home, the landmark report into the separation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children from their families was, and following Moffatt’s relocation to New York City. The twenty-five-part monochrome photographic series is set against the backdrop of a harsh Australian desert town. The series appears to comment on race relations between Indigenous and non-Indigenous community members. However, Moffatt indicates that the series does not depict but implies a narrative, allowing the viewer to fill the empty space with their own assumptions. Up in the Sky #12 features an Aboriginal child dressed in a nurse’s uniform in a barren landscape. The image raises more questions than it answers: has this child been forcibly removed and trained as a housemaid or are they in costume and happily playing?

1 N King, Fall in to my fiction, My Horizon, Thames and Hudson Australia, 2012, pg 2

Yhonnie Scarce

born 1973, Woomera, South Australia

Kokatha and Nukunu people

Florey and Fanny 2011

hand-blown glass, cotton aprons

City of Yarra Council Collection

© the artist

Yhonnie Scarce is a Kokatha and Nukunu artist and curator based in Naarm/Melbourne, Victoria. Working with glass, photography and found objects, Scarce’s practice explores the ongoing intergenerational trauma of colonisation on Indigenous Australians. She draws on her family record and memory to present installations and public art monuments that draw attention to suppressed histories including the British nuclear tests in central South Australia, the relocation of Aboriginal people from Country, and the Stolen Generation.

Florey and Fanny (2011) pays homage to Scarce’s Nukunu ancestors and family members, her great-grandmother Florey and grandmother Fanny specifically, who were domestic servants in the early 1900s. Scarce represents these matriarchs through their domestic uniforms, and reasserts their identities by sewing their names onto the garments. Hidden in the pockets of the uniforms are hand-blown glass bush plums. Scarce uses bush tucker – bananas, plums and yams – as metaphors and representations of Indigenous bodies, and the body of Country. Here the women secretly carry the bush plums as a means to maintain connection to their Nukunu culture. The visible stems of the fruit, piercing through the cotton aprons, signal that colonial control will never be strong enough to suppress a sovereign woman’s cultural identity and connection to her community.

Julie Dowling

born 1969, Subiaico, Western Australia

Badimaya people

White with one 2003

synthetic polymer paint and red ochre on canvas

Collection of Elizabeth Laverty

© Julie Dowling / License by Copyright Agency 2021

Julie Dowling is an artist of Badimaya, Irish, Scottish and Russian ancestry who works with the European tradition of portraiture to illustrate the oral histories of her family and Badimaya community. Considered a master storyteller, her social realist painting practice recontextualises the history of Australia’s colonisation to present the perspectives and experiences of First Nations people. She utilises colonial records such as photography and archival documents to seek truth-telling around issues of the Stolen Generations, indentured labour, and Aboriginal culture’s ongoing survival.

White with one is a powerfully moving reminder of the unjust treatment of young Aboriginal girls and women who were removed from Country and community to live in government-run facilities where they were trained for domestic labour. Dowling comments on her own family’s history:

Most members of my family have at some time in their childhood been forced to work for no pay. Working on pastoral properties as domestic servants and farmer’s labourers they worked hard. Under the 1905 act Indigenous people were not allowed to keep money from any jobs they had. Their money (if any) was deposited with the protector of Aborigines at the time kept in the state banks. This money has become a contentious issue with the [Liberal] Government of Western Australia. Because without adequate compensation for the work they did it would be seen as slavery in the modern era by a developed first world country…. Most of these children and adults worked from sun-up to sun-down and received bad housing and food. Many children still suffer the physical and psychological effects of abuse while working for nothing.1

1 J Dowling, artist statement, Artspace, Perth, April 2021, pg 4

Natalie Harkin

born 1970, Adelaide, South Australia

Narungga people

Archive-Fever-Paradox 2013

ink on banana leaf paper

On loan from the artist

© the artist

Natalie Harkin is a Narungga woman, artist and poet based on Kaurna Yarta, Adelaide, South Australia. In 2017 she completed a Doctorate of Philosophy, School of Communications, International Studies and Languages at the University of South Australia and is currently Senior Research Fellow in the Indigenous Studies team, College of Humanities, Arts and Social Sciences at Flinders University. Harkin’s research and creative practice seeks to decolonise the colonial archive by engaging strategies of ‘archival-poetics’ to investigate South Australia’s Aboriginal women’s labour stories. She is a member of Unbound Collective which was formed in 2014 with colleagues Ali Gumillya Baker, Faye Rosas Blanch and Simone Ulalka Tur.

Harkin’s Archive-Fever-Paradox (2013) repurposes copies of her family letters, held in South Australian state archives, which formed the basis of her PhD research. The letters were written by her grandmother and great-grandmother and sent to institutions and staff of the Children’s Welfare Department and the Aborigines Protection Board. Harkin shredded and then wove together copies of the letters using a Ngarrindjeri weave. The exterior of the basket has been embellished with key words and phrases from the letters such as “a domestic”, “kitchen work”, “identity card”, “cleaning”, “house maid”, “my daughter”, “we would all like to have her home very much”, “I would like to meet her”, and “down hearted”1, which distil the sentiments found in the correspondence. In this way, Harkin honours the Aboriginal women in her family and offers a ‘counter-narrative’ to the ones told by state authorities.2 A basket of grief becomes a love letter to her children of all that our ancestors carry.

1 N Harkin, Weaving the colonial archive: A basket to lighten the load, Journal of Australian Studies, 44(2), pp154-166, 2020, accessed 16 September, <https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/14443058.2020.1754276>

2 N Harkin, personal correspondence with M Reece, 22 September 2021

Artists Unknown

Hermannsburg (Ntaria), Northern Territory

Dressing table set 1943

embroidery on cotton

‘Tea time’ tray set c1930

embroidery on cotton

Cake cloth or sandwich tray c1930-1940

embroidery on cotton

Untitled (apron) c1950-1960

embroidery on blue cotton

Untitled (apron) c1950-1960

embroidery on grey cotton

Gift of Helene and Dudley Burns from the collection of

the late Reverend and Mrs F W Albrecht 1988

Collection of Flinders University Museum of Art 2746, 2747, 2748, 2749.001, 2749.002

This collection of embroidered textiles was created at the Hermannsburg (Ntaria) Mission in the early-mid 20th century by Western Arrernte women who were introduced to needlecraft by Frieda Strehlow and later Minna Albrecht, the respective wives of subsequent mission superintendents Pastor Carl Strehlow and Pastor F.W Albrecht. Learning to embroider, quilt, crochet and sew, these women – who were paid a modest income for their labour – produced textiles of exquisite quality that were sold in Alice Springs and further afield to provide much needed income for the Mission.

Some of the earliest techniques included open and closed whitework which produced lacy effects as well finely stitched crochet and quilting. Later, textiles were embellished with colourful chain and cross-stitched embroidery often depicting Australian flora and fauna, as well as Aboriginal motifs such as boomerangs, coolamons, and clapping sticks. Many of these designs were copied or adapted from Semco patterns. These patterns were purchased from retailers such as Myer and John Martin's in Adelaide and sent to the Mission.1

1 R Ellis, personal correspondence with M Reece, 19 July 2021

Flinders University Museum of Art

Flinders University I Sturt Road I Bedford Park SA 5042

Located ground floor Social Sciences North building, Humanities Road adjacent carpark 5

Telephone | +61 (08) 8201 2695

Email | museum@flinders.edu.au

Monday to Friday | 10am - 5pm or by appointment

Thursdays | Until 7pm

Closed weekends and public holidays

FREE ENTRY

Flinders University Museum of Art is wheelchair accessible, please contact us for further information.